During the spring/summer of 1917, when most able-bodied, male Canadians were fighting and dying in battles like Ypres, the Somme, Vimy Ridge and Arleux, another Canadian faced a death that wasn’t related to warfare or the Spanish Influenza that slowly wound its devastating path around the world. This man’s name was Tom Thomson.

Tom Thomson was a son, brother, fiancé, friend, a naturalist, park guide, recluse, secretive, shy, an enigma, and hailed as one of Canada’s greatest painters. He was notoriously secretive and so insecure of his work that even those who knew him rarely saw what he was working on.

The mystery surrounding his death has overshadowed many of the puzzling details of his life. How did one man, with no training or apparent skill suddenly burst into the art scene and within a 4-year period paint so many iconic works of art? How did such a sickly child who stayed at home from school because of a respiratory ailment, find himself spending most of his time as a rugged outdoorsman exploring and painting in Algonquin Park?

Born in 1877, Thomson grew up on a farm near Owen Sound with a family that loved and encouraged the arts. He sketched and painted on occasion but produced nothing that suggested a future as a critically acclaimed painter. He was considered an average kid who suffered from health problems. And, it was these health problems that kept him out of both the Boer and Great Wars.

Tom’s foray into the working world had a rough start. Undecided on what he wanted to do after being rejected from serving in the Boer War, he worked briefly as a machinist in Owen Sound. Not long after taking this job, he packed up his bags and moved to Seattle to be with his brother, George. Here he worked as a commercial artist for Maring and Ladd and later Seattle Engraving Co. until an awkward courtship misunderstanding sent him running back to Canada. When he returned, he worked as a senior artist for Legg Brothers Graphics Ltd, a photo-engraving firm (now a graphic design firm) in Etobicoke.

The turning point in his life came in 1909 when he took a job with Grip Limited, another Toronto design firm founded in 1873 by the cartoonist J. W. Bengough. It was here that he met his closest friends: Jim MacDonald, Arthur Lismer, Frederick Varley, Franklin Carmichael, Frank Johnson, and later Lawren Harris and Alexander Young Jackson. These are the men who would later go on to form the Group of Seven, Canada’s first national art movement. The group believed that distinctive Canadian art could be created by becoming one with nature. And, if not for Tom’s untimely death, the Group of Seven would have likely been the Group of Eight… or simply the Algonquin School of painters.

Lawren Harris wrote in The Story of the Group of Seven, that Thomson was “a part of the movement before we pinned a label on it” and that two of Thomson’s paintings The West Wind and The Jack Pine are two of the group’s most iconic pieces. These men spent a large portion of their painting time in Algonquin Park and the countryside surrounding Toronto. Eventually, Thomson would come to settle in Algonquin Park, living in a tent and only returning to a rustic, shack-like studio when he needed to consolidate his art.

The West Wind and The Jack Pine are currently both in the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO).

The West Wind (1917)

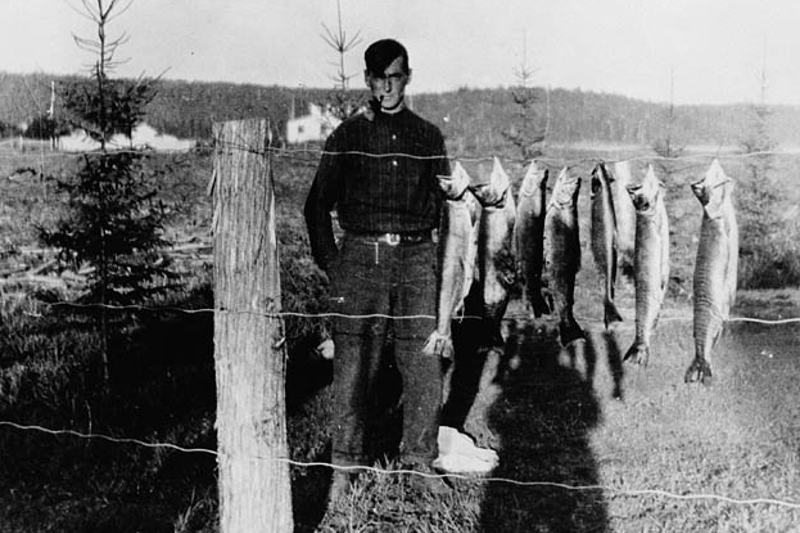

The West Wind was found resting on Thomson’s easel after his death in 1917. During the summer of that year, he worked as a guide and forest ranger in Algonquin Park, spending large swaths of time fishing, paddling in his canoe, and vanishing into the woods.

While out in the woods, Thomson would create small oil landscapes on portable canvases. He would then bring these back to his cabin and recreate the sketches on a much larger canvas. He didn’t think that the oil sketches had much value and would give them away to anyone who asked for them. But as time passed, these became items of value because they were painted at the moment. They are rapid-fire representative of an experience. Whereas the larger landscapes would leisurely evolve in his cabin.

Thomson wasn’t a master or technical draughtsman; his paintings have a rugged and almost child-like level of accuracy. The magic comes with the colour that he created and folded into the paintings. He is considered a master in this regard.

The Jack Pine (1916-17)

Both The Jack Pine and The West Wind are paintings of one pine tree. The two are rarely shown together but are now hanging side by side in the Art Gallery of Ontario. They are hailed by critics as “bold statements of national identity, resilience and belonging in nature.”

I don’t think that Thomson saw his paintings in this manner. He often said that he only painted what was there and proved this through photographs. But what he did do, was take these images and layer in colour and detail that he saw as a naturalist, but was not easily seen by others. With The Jack Pine, he recreated a dry, barren, broken old tree and brought it back to life.

To this day I can’t look at a scraggly, barren pine tree and not mentally transform it into a Thomson painting.

The Mystery of his Death (1917)

On July 16, 1917, Tom’s body was found on the bank of Canoe Lake with a 10 cm gash on his right temple and with his foot wrapped with tangled fishing wire. The official ruling by the medical examiner was death by accidental drowning.

However, many observers, friends and family have disputed this claim. His body was found by a doctor who claimed that air came from Tom’s mouth during the initial examination of the body and that there was dried blood in one ear. The fishing line was wound around only one foot several times as though the body had been weighed down. Observers noted that there was no evidence to indicate that Tom was fishing or paddling because there was no gear or a paddle that was ever found in the calm lake.

Those who lived in Algonquin Park have long claimed that Thomson was murdered… possibly by Shannon Fraser, the Postmaster of Algonquin Park and owner of Mowat Lodge where Tom stayed occasionally but visited often. On the night before Thomson was noticed missing, two men argued about money — possibly because Tom wanted to marry a local woman, Winnifred Trainor, and needed the money to buy a suit. During the argument, Shannon punched Thomson in the face and knocked him backwards into a fire grate. Tom never got up. This would explain the gash on his head and also the blood in his ear, which would have remained because it dried before he was put in the water.

Fraser’s wife, Annie, confessed to a friend (Daphne Cromby), the medical examiner, and again on her deathbed that her husband killed Thomson and that she helped tie Tom’s feet with fishing wire, put him into his canoe, and dump the body into Canoe Lake. Shannon Fraser pointed his own finger at Martin Blecher, an unpopular German man who lived in the area and had a penchant for assaulting people with a canoe paddle. Fraser also started rumours of suicide that were unsubstantiated.

As you dig deeper and deeper into the mystery, what you discover is an extremely small, tight-knit community of people who knew each other, fought with each other, lied to protect each other, and who argued like a large, dysfunctional family. Everyone seemed to know the truth, but no one wanted to pursue it. The real tragedy comes with the lack of character and decorum shown by many of the people involved (especially after the death of Thomson), the loss of the art that could have been, and the impact of Tom’s death on the life of Winnifred Trainor.

It’s a real Canadian tragedy.