On the 100th year anniversary of the Great War battles that defined Canada as a nation, I remember my great-great uncle, Samuel Maxwell McKinnon and the friends who surrounded him. He’s one of my favourite family members to research because I keep finding new information about him as I peel away layers… like an onion… and with each layer, his life and personality becomes more three dimensional and complex.

Max also periodically pops up in many of the places I’ve lived or travelled: England, France, Saskatchewan, Calgary, Manitoba, and Nova Scotia. I feel like he is a kindred spirit and it makes me sad to think that he, like so many other men of fought in the Great War, never completed their right of passage or lived to experience all the big changes that happened between the 1920s and 1960s.

His life was snuffed out quickly and like so many from the Great War, he was forgotten and lost to the mists of time until my grandfather (also named Maxwell) found a picture and started to search for more information about his namesake. He interviewed relatives, talked to locals, kept handwritten notes, but he did not have access to archives, historical records, or the internet like we do today.

Many times he shared family history with me while sitting in the family graveyard in Mill Village. These moments are precious, but they are not historically complete. I am continuing his search for information about Max and have spent the last few years travelling and researching this post.

Nova Scotia: Village Boy Origins

Born on April 20, 1895, Max spent most of his youth in Mill Village, Nova Scotia. He was 5’10 1/2, looked like his mother, and inherited the same blue eyes that I share with my great grandfather (Max’s brother). The house that he was born in and lived in is still in Mill Village.

Max’s life is intertwined with that of another local boy: Amos Brenton Leslie (born August 15, 1891). Max was four years younger than Amos but happenstance brought them together and in a small community like Mill Village, they likely knew each other their entire lives.

In 1901, both were living at home with their parents: Max with David and Martha, and Amos with John and Ellen Leslie. By the 1911 census, Max was working as a labourer and living at home… and Amos appears in the 1910 United States Census for Stirling, Massachusetts; he worked as a dairyman for George and Idella Fitch. According to the census, he immigrated to the U.S. in 1907, when he was 16-years old.

It was here that he met his first wife: Edith Anne Keizer, daughter of Henry and Emily Keizer, both from Canada. Amos and Edith married on May 18, 1912, in Northborough, Massachusetts, United States and had a daughter 4-months later on September 10, 1912.

Edith Leslie died less than 2-years later on January 11th, 1914. Death records show that she died of pneumonia a day after giving childbirth to their son (Henry Theodore Leslie)… at 23-years old.

Shortly after Edith’s death, Amos migrated back to Canada. He left a daughter behind with Edith’s parents in Northborough where she lived with her grandparents and then her uncle until at least 1930 when her digital footprint disappears.

Saskatchewan: The Migration West

By the time of the 1916 Saskatchewan census, Amos was living with his brother Harry on a homestead outside of Cabri in Saskatchewan. The community was called Fosterton, named after one of the homesteaders (Foster) who requested the name change when the railway went through.

Originally the area was called “Scotia,” possibly after Nova Scotia, where many of the young Mill Village men who settled in the area came from. The last remnant of the original name is still seen in the Scotia school, which still sits on a parcel of property purchased by Henry Leslie who worked hard to bring a school to the community.

In 1909, Henry Leslie moved West as a “green” youngster with the Saskatchewan Valley Land Company and their grand scheme of settling the prairies; this is a common theme in both the history of Saskatchewan and Alberta and many from the East (including Stanley Coops) headed west for the cheap land.

Homesteaders could purchase 160 acres (a 1/4 lot) for $10.00 and they had to “prove up” before they were given the deed to the land. “Proving up” means that they needed to break at least 10 acres of prairie a year for three years. The land needed to be occupied for at least 6 months of the year and a dwelling ($100 in value) needed to be on the land. Land taxes were $3.60 per year.

Harry applied for and settled on two plots of land given the SW 2 18 18 W3 and NW 2 18 18 W3 distinction. The SW plot is in the 1916 census and Harry is listed as the head of his household. According to the census, living with him is his wife Phenie, his son Harold, his brothers Amos and Carmen, and his brother-in-law, Arthur Norman Joy (both Arthur and Amos are labelled “C” for Camp Hughes).

The neighbours listed on the census (in the NW plot) are Eugene (Gene) Freeman, his wife Beda, and their son Elton. With them were living Gene’s father Ambrose, Beda’s mother Johana, and a lodger.

There is more to the story than the census has to offer. And, through a personal history written in 1983 by Phenie Smith and her son Harry Leslie, we are able to see a community built by homesteaders, Americans, Norwegians, and a contingent of boys from Mill Village.

Eugene and Harry are childhood friends from Mill Village who came West together and applied for grants together. In order to afford both plots of land (in Harry’s name) the two would swap time in and out. One would stay in Saskatchewan and work the land while the other would go back to Nova Scotia to earn the funds needed to keep the farm going.

They continued to do this and periodically brought back “boys” from the East to help with the harvest. In 1915, Amos Brenton Leslie, Carmen Joseph Leslie, and Gene’s cousin, Max McKinnon came to Saskatchewan to help.

“Harry’s two younger brothers, Amos and Carmon, and several other young fellows came out for harvest. Later Amos worked on a threshing crew and Carmon worked for us.

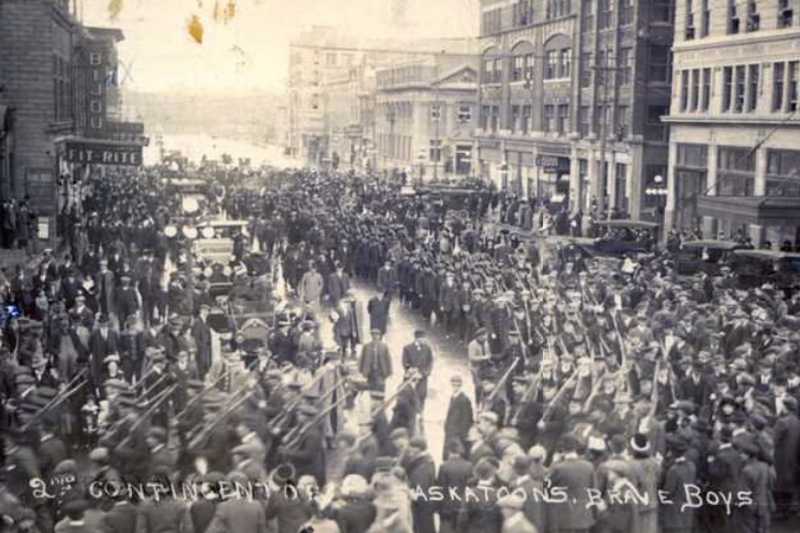

After harvest, Harry’s brother Amos, my brother Arthur, Archie Battrum, and a couple of other boys who had come from the east for harvest, Max McKenon (Gene Freeman’s cousin) and Jack McKeekern from Prince Edward Island, all went to Swift Current and joined the 209th Battalion. Carmon Leslie went to Calgary and joined the Light Horse Cavalry, but he never got overseas — the rest did. Amos returned from overseas after the war, but never came west again.” – Phenie Smith (River Hills to Sand Hills: a History of Pennant District. 1983. Pp. 483)

Attestation: Those Who Served Overseas

So, what happened to all these boys mentioned by Phenie Smith? “The Boys” attested together on March 9, 1916, as a group and joined a newly formed battalion: the 209th Battalion from Swift Current, Saskatchewan.

At this point, enlistment was still voluntary in Canada; however, recruitment was aggressive and paid for the people of Swift Current. Peer pressure was intrusive and people who avoided enlistment were outed in the local newspaper. During a recruitment meeting in Cabri, officers called the people of Cabri un-patriotic and apathetic because they weren’t giving up their farm working sons.

To complicate matters, on March 2nd the Military Service Act of 1916 was implemented in England, which allowed the British government to call upon all single, able-bodied men for service. In 1916, Canada was still a Dominion of the British Empire and wasn’t able to make it’s own wartime decisions (not until 1917). As such, the boys may have faced further pressure to enlist even though it was not legally required.

Cabri acquiesced. The diagram below shows the line of Cabri boys as they attested on March 9 in Swift Current. The gaps in numbers were filled by others from Webb, Saskatchewan, which is an hour away from Cabri. I could not find a link between the two groups other than both towns being targeted heavily at the same time by the “recruiting trains.”

Carman Leslie did not attested with the group; he later joined the CEF on October 26, 1917 and became a part of the 1st Battalion in Regina. Married men were not initially required to join (Henry and Gene); but, they were impacted by the war as much as those who served, as you will see.

Max McKinnon (Regimental #252419)

As mentioned above, Samuel Maxwell McKinnon is my great-great-uncle. On enlistment, he was 20-years old, 5’10 1/2, 175 lbs, healthy, and single. Family members remember him as being well-liked, vibrant, and independent.

There is no record of Max in the 1916 Saskatchewan census but he was obviously in Swift Current on March 9, 1916, when he signed his attestation papers, enlisted, and received his Regimental number.

On April 17, 1916, Max sent a photo postcard from Swift Current to the McKinnon family in Nova Scotia. The message on the back was to his father: Dear father: Just a card to let you know I am well hope you are the same. From Max.

After attestation, soldiers from the 209th spent their time in Swift Current doing basic training and waiting for the battalion to reach full strength and get the order to move to Camp Hughes. The Imperial Hotel was converted into a barracks and it was here that they stayed until June 1, 1916.

Amos Leslie (Regimental #252420)

Amos Brenton Leslie was standing behind Max in line and received the next regimental number. He is listed in his attestation records as being 5’11 1/2 inches tall, with brown hair and brown eyes, and sporting a tombstone tattoo on his right forearm.

As mentioned above, he was a widower and had a 5-year old daughter named Edith May, for whom he sent $20 a month in Separation Allowance. For widowers with dependent children or mothers, soldiers could send a portion of his pay, which was matched by the government, to ensure they had income while the breadwinning parent was away.

Jack McEachern (Regimental #252422)

John Thomas McEachern was from Rice point P.E.I. and was one of many children born to Alex and Ellen McEachern. He was 5’11 with a fair complexion and blue eyes.

How did a 26-year old man from a tiny little town in P.E.I. get mixed up with a group of boys from Nova Scotia who had known each other their entire lives?

Jack came to Saskatchewan for the same reason that Henry Leslie came: land. He petitioned the Saskatchewan Valley Land Company and applied for two lots next to the Leslie family and was awarded SE 1-18-19-W3. Jack was the neighbour to the East of the homestead; and later, his mother Ellen became the landholder.

Archie Battrum (Regimental #252418)

Archibald Thomas Battrum was in line and in front of Max when the boys attested in Swift Current. He is listed as being 5’10 inches tall, with a fair complexion and blue eyes. His birthplace was in Middlesex, England (some sources say Hendon and others say Willesden). In the early 20th century, Middlesex was a county located outside of London. It has since been absorbed by the city and no longer exists.

In 1906, Archie’s father William (born in Paddington, London) applied for and was granted land in Saskatchewan. The first years were difficult and not as idyllic as the Battrum family were led to believe. In 1907, Archie’s mother arrived in Saskatchewan with six children; unfortunately, they all arrived with diphtheria and only two survived: Archie and his brother Frank.

When the railway came through William’s farm, officials named the community “Battrum,” which still holds; the town is known for its iconic row of grain elevators. A few years later Archie applied for his own parcels of land: SW 10-42-19-W2 and NW 33-41-19-W2.

Arthur Joy (Regimental #252499)

Arthur Norman Joy was an 18-year old from Detroit Lakes in Minnesota. He moved to Saskatchewan in 1911 with his widowed mother and siblings. They followed other family members who purchased and settled on homesteading land between 1909-1910. Mrs. Lena Joy (eventually Bergset) settled on a quarter section located at SE 15-18-18-W3. This was close enough to the plot settled by Harry Leslie and Gene Freeman that the two families became closely intertwined with each other. In 1916, Arthur was listed on the Leslie family census records.

Arthur attested twice to the same unit (the 209th), once in Saskatchewan (March 16th, 1916) a week after all the other Mill Village boys… and once in England (Dec 14th, 1916). On enlistment, he was described as 5 feet 8 1/2 inches tall with dark skin, brown eyes, and brown hair. He had a scar on his left eyebrow and another running into the right corner of his mouth.

There are gaps in Arthur’s military records. According to the family, he lied about his age in 1915 to join the military; this is not reflected in any of the CEF documentation. Also, the vast majority of the documents come from after January 26th, 1917. On this date, Arthur deserted the military.

Arthur was back in Aldershot by February 1917 and is hospitalized right away for a month… because he contracted gonorrhea.

According to his medical records, he suffered from this or some symptom of it for the rest of his time in the service. It wasn’t until 1937 that antibiotics were used as an accepted treatment for gonorrhea. Before this, heat therapy and the use of sulfonamides or metals would have been common.

Those who Stayed Behind

While there was still pressure from the community to enlist all able-bodied men, those who were married were not pushed to serve.

In the early years of the Great War, this is a good thing because women and children had very few legal, financial, or property rights. Thus, if a husband died, the family and their means of income were often left to the mercy of the courts. And, the probability of death during the war was high.

Neither Harry Leslie nor Gene Freeman served in the Great War but they were still impacted by it.

Gene Freeman

Eugene Ellis Freeman was the first son of Ambrose and Lavinia Freeman (nee McKinnon). Lavinia’s brother was my great great grandfather, David McKinnon (Max’s father), which makes Gene and Max cousins.

Gene did not enlist in the military to become a part of the 209th like the other boys. But, this didn’t mean that he didn’t face wartime challenges. On December 6, 1917, while having breakfast at a Halifax hotel by the harbour, Gene and his wife, Bada, became victims of the Halifax Explosion.

Bada was one of the thousands permanently injured in what has been described as a blizzard of glass. She lost an eye and would have debris from the explosion in her body for the rest of her life. Eye injuries were one of the most common injuries from the explosion; because people were watching the collision from their windows.

Gene was not permanently injured in the blast but like so many people who survived the explosion, he was left to fend in a decimated city… just as a huge Nova Scotian blizzard hit.

The couple eventually made it back to Saskatchewan and back to live their lives on the Prairies.

Harry Leslie

Harold Theodore Leslie and his journey to Saskatchewan is well documented in the narrative above; he married Phenie Elizabeth Joy Leslie Smith and the couple had a son named Harry, a daughter named Hazel, and a daughter who died within the first 24-hours after birth.

Harry was not one of the men who served in the Great War; but, his life was impacted by a bigger disaster that many returning soldiers brought back with them: the Spanish Influenza.

The flu hit Swift Current and surrounding countryside in the fall of 1918. The first reported death came on October 19th and the following wave consumed the community. It was fast and swift and the total time from the first death to the point when newspapers announced that there were no new cases in the community (Nov 12th) was 24-days.

I couldn’t determine from newspapers and records how many people died in the first wave; many deaths were not reported but every day the newspapers listed dozens of people who had passed… some from other cities who were visiting relatives. The flu affected mostly healthy adults and in the span of a month, many children in the community were orphaned.

No one from Harry’s family perished in the first wave. However, a second wave hit during the first week of December and Harry succumbed to the flu on December 6th, 1918.

Gene Freeman and George Bergset (Phenie’s father) were the joint executors of Harry’s will. The total value of the estate was $12,662.55, which in today’s dollars is roughly a quarter of a million dollars. Fortunately, Harry died in 1918, after women had earned more rights thanks to the work of suffragists, the Conscription Crisis, and a shift in public sentiments; so, Phenie was able to keep the land in Cabri.

Unfortunately, the estate wasn’t fully resolved until 1925; Henry’s brother Carmon and several creditors made claims against the estate, Harry had just rented out his land for use to another farmer named Roy Cole (until 1923), and Harry was in the middle of buying a portion of school land from the province.

Carman Leslie (Regimental #3354740)

While Carman Joseph Leslie served in the CEF, he never left Canada and he wasn’t a part of the 209th Battalion. He was conscripted under the Military Service Act of 1917 on July 9th, 1918 in Regina. On enlistment, he was described as 5 feet 8 1/2 inches tall with grey eyes and brown hair.

The Remembrance Series

But wait… there’s more! The following posts follow the Mill Village Boys on their journey through the war.

World War 1: The Mill Village Boys (Part 1)

World War 1: the 209th Waiting in Swift Current (Part 2)

World War 1: the 209th Training at Camp Hughes (Part 3)

World War 1: the 209th Waiting in Digby (Part 4)

World War 1: the 209th’s Journey and Arrival Overseas (Part 5)

World War 1: the 9th Battalion in Shorncliffe (Part 6)

World War 1: the 9th Reserve in Bramshott (Part 7)

World War 1: Taken on Strength… to France (Part 8)

Arleux-en-Gohelle (a.k.a Finding Max)

The Dominion British Cemetery (a.k.a. Finding Jack)