This is the third post in a series about a group of World War 1 soldiers from Mill Village, Nova Scotia who all enlisted for the 209th Battalion in Swift Current, Saskatchewan. For full context and more information about the people below, Part 1 is here. There is also a remembrance page with links to all the posts in this series, which can be found here.

Carberry, Manitoba (June 1 – August 15th, 1916)

“This is going to be a great camp there are about 20,000 men here already.” – June 5th 1916, Corpl A. W. Mayse. 222nd Battalion C.E.F. Camp Hughes

The 209th boarded a train on June 1st and were moved en masse to Camp Hughes in Carberry, Manitoba. Camp Hughes replaced Camp Sewell, which focused primarily on cavalry training.

Camp Hughes was designed and built to mimic life in the European trenches; one of the early discoveries in the war was that without proper trench system training, soldiers struggled to physically and mentally survive on the Western Front.

So, for the men in 1916, they were given the opportunity to train in trenches dug by combat veterans who survived the early years of conflict.

This was the first taste of the wartime life and hardship for these men (minus the smell, the death, and the weapons… there weren’t enough weapons to go around). And, to put this into historical context, these are the same men that would go on to fight at Vimy Ridge.

On June 4th, 1916, Bob Galloway from the 209th Battalion writes about those first days:

We are at Sewil [Camp Sewell] now came down on the first haven’t been doing any thing mutch since mostley mess parades and church parades I gess we will get it tomarrow good and hard some way they feed us to we usually get half what we are suposed to get some times not that some body is making monney some where and we get the benefit I gess not it is all sand aronnd hear we sleep in the sand eat sand wash dishes in sand and some men shave in sand…

At this point, Camp Hughes was instantly a city bigger than most cities in the West. 30,000 men arrived all at once from all three prairie provinces to live, sleep, train, and fight. This is roughly the equivalent of the population of Regina in 1916 (Calgary had a population of 56,514, Saskatoon 21,048, and Winnipeg 163,000).

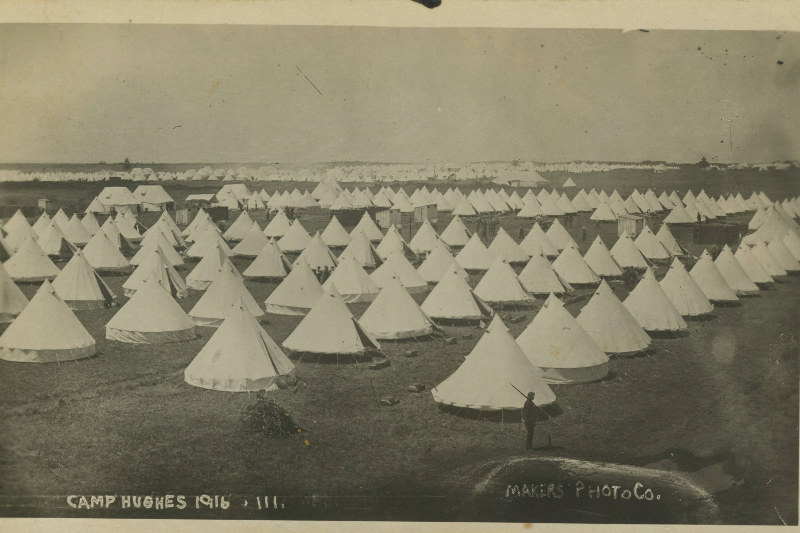

The Camp Hughes tent city was massive and reportedly stretched as far as the eye could see. Below is the 209th Battalion’s section of tents (small in comparison to others).

Each tent contained ten soldiers from one platoon. Bob Galloway describes this: “we sleep in Beel [bell] tents about 12 feet across 10 in a tent packed in like saridines [sic].”

Camp Hughes wasn’t just made up of tents. There was the main street (called the midway) that contained a post office, six movie theatres, a hospital, a photo studio, and a variety of retail stores. There had to be a lot of activities available to keep both the men and their visiting families entertained in the middle of the Canadian Prairies. This was a tremendous money-making opportunity for locals.

Behind the 209th tent, a section was the camp swimming pool, which can be seen in the photo of a tent above (early morning steam shows in the left-hand side of the photo).

In 1916, Camp Hughes had the largest outdoor heated swimming pool in Western Canada. Battalions organized regular swimming “parades” that would have provided a welcome relief from the daytime summer prairie heat… especially after a day of training in the trenches.

Like mentioned above, the troops in Canada did not have enough weapons to train all men on their proper use. Instead, they carried wooden guns while the officers used the real weapons with blanks to expose soldiers to the sights and sounds of war. Blanks, smoke, and bombs were used to mimic life on the Front as closely as possible during training sessions.

Thomas Johnson writes on October 6th, 1916:

“We spent the last two nights in the trenches, using bombs and blank ammunition. The first night it was wet & miserable, & we spent part of it on guard & part of it in a dugout. Most miserable business. The next night we were the attacking party. That was better. To see the flash of the rifles from the defending trenches, & the blaze of light when a bomb exploded was just wonderful. Of course, it was dark, with a little moonlight, but it showed up like a moving picture show.”

The Mill Village Men at Camp Hughes

One of the people in the same Battalion as the Mill Village Men was George Glen Mooney; the photo below was donated by his family to the Military Museum in Ottawa.

I believe it is from the time when the men were in Manitoba because the building in the background shows up in the officer’s Christmas cards for 1916, it is during a warm and dry part of the year (look at the grass), and, none of the Mill Village / Swift Current men were in Europe during this period (so it can’t be from Shorncliffe or Bramshott).

I ran it through facial recognition software and later verified the results with osteological mathematical measurements and overlays of known photos.

Three of the four men who attested together in Swift Current are standing in the back row.

Archie managed to elude the software. It’s possible that he wasn’t in the photo. There is a period between June 24th and July 2nd when he was hospitalized at Camp Hughes with “severe” tonsillitis.

Every Battalion at Camp Hughes during the Summer of 1916 had a professional photo done of both the Battalion, the Company, and their tent area. The 209th is below from two different vantage points. Military leadership is in the front and each of the four Companies are standing together. Our men are in Company “B” and Arthur Joy is in Company “C.”

I’m still working on identification in these photos. I have high-resolution copies that show each individual face, but because of the distance and shadowing it’s more difficult to apply measurements. Instead, I am working backwards and eliminating who couldn’t be the Mill Village men (height, shoulder size/angle, and obvious features like ears and chin); this is taking time and I need to access the original photos in the archives (in progress).

There is one grouping of men whom I think are good candidates… but more work is needed. I don’t want this identification to hold back the rest of this post.

Fall Harvest (August 15 – September 30, 1916)

One of the agreements made at the start of the recruitment drives was that the men of the 209th would be granted time in the fall to go home and work the harvest. As mentioned in Part 2, the arrival of the recruiting trains meant losing young farm labour just as international demand for wheat increased because of the war. This problem was later solved by the Federal creation of “Soldiers of the Soil” (SOS) and local “Farmerettes” programs that recruited high school students to help work the land.

On August 15th, about half of the men at Camp Hughes (15,000) were given leave to go home for the harvest. They were due back at the Camp on September 15, 1916, but this leave was eventually extended until September 30th, 1916 (after initial rejection). In order to take advantage of the opportunity, an application needed to go to the commanding officer. From the Mill Village group of men, all took leave.

Max took the least amount of time (5-days) and may have stayed behind initially or come back early to take one of the many extra training courses that were offered during this period. All the other men took roughly 2-weeks. None were paid by the military during this period; all were considered absent with leave.

In late September, the men received orders to return to Camp Hughes.

Final Medical for Embarkation (October 6th, 1916)

Before departing, the men were required to go through a “final” medical exam at Camp Hughes to determine whether they were fit for service. This caused a significant amount of stress for some of the men, particularly when it came to the main physician: K.C. Cairns. Many wanted to go overseas and serve but lived in fear of being deemed unfit for service.

Kelso Carmichael Cairns was the main physician serving for the 209th Battalion. His name appears on just about every soldier’s paperwork, even that of Thomas William Johnson, the Methodist minister for the Battalion. Johnson got a second medical by another doctor and later wrote in a letter to his future wife: I have always been glad that I got Dr Graham & not Dr Cairns to examine me. I feel very hopeful about the result whereas I would have been afraid.

Another soldier from the 209th, Bob Galloway, writes: “I passed the final medical examination yesterday and I was vaxanated to day so I have seen enough of the doctor for a few days there was only about 6 turned down in the hole Batt mostly the Big men [?] all the big men were unfit…”

Through all the research I’ve done, I’ve wondered if there was a reason for Max’s two recorded AWLs (in September and October). Both coincide with the timing of medical board exams. Type 1 diabetes is prevalent in our family and Max’s mother Martha is known to have suffered tremendously. Also, in the few photos I have of Max, he has a slight lean to the left, as if one of his legs is shorter. Would either of these preclude him from service? Who knows. It’s speculation.

What isn’t speculation is that there was a mandate with the 209th Battalion to push soldiers through the medical exams in order to make battalion quotas. Nic Clarke writes in Unwanted Warriors: Rejected Volunteers of the Canadian Expeditionary Force:

“…commanding officers who were desperate to fill their ranks took men without any medical examination at all. There were many ways of managing this. In some cases, officers ensured that medically questionable men were absent when medical board examinations were carried out; in others, they enlisted men after these examinations had taken place.”

“Lieutenant-Colonel W.O. Smyth, Officer Commanding 209th Battalion, certified that all men in his unit had been medically examined and found fit for service before embarkation for Europe. It was later discovered, however, that over a hundred men (approximately 10 percent of the battalion’s strength) had been absent when the unit’s final pre-embarkation medical inspection was done. Smyth falsified his documentation in order to bring all his men to Europe.” (Unwanted Warriors, Page 67)

This is the path that Arthur Joy followed, and there is a paper trail to support it. Arthur’s sister Phenie Smith wrote in River Hills to Sand Hills: a History of Pennant District that her brother was originally rejected from service in 1915 for being too young. However, I could not verify this.

Church records from Detroit Lakes have Arthur recorded as being born in February 1898, which made him 17-years old in 1915… and there were plenty of 17-year olds joining the CEF at that time. Some as young as 15-years old appear in the records (e.g. James MacDonald Minifie enlisted at 15-years; deemed fit for service by K.C. Cairns).

Perhaps there was another reason he was rejected.

Arthur was declared fit for service on March 16, 1916, by K.C. Cairns; however, during the final medical exam at Camp Hughes, Arthur was rejected by the board.

But, miraculously, even though he was declared medically unfit and sent back to Camp Hughes, Arthur left on the train with the rest of the men, was on the Caronia on November 1st when it left and was in Shorncliffe on November 11th when the troopship arrived. And, on December 14th, 1916, K.C. Cairns declared Arthur Joy “fit for service” and he re-attested in England.

There is more research pending on this topic.

Off to Nova Scotia (October 9th, 1916)

The battalion left by train on October 9, 1916, to Nova Scotia. From Halifax, they would board a troopship and head to Shorncliffe in England.

The Remembrance Series

But wait… there’s more! The following posts follow the Mill Village Boys on their journey through the war.

World War 1: The Mill Village Boys (Part 1)

World War 1: the 209th Waiting in Swift Current (Part 2)

World War 1: the 209th Training at Camp Hughes (Part 3)

World War 1: the 209th Waiting in Digby (Part 4)

World War 1: the 209th’s Journey and Arrival Overseas (Part 5)

World War 1: the 9th Battalion in Shorncliffe (Part 6)

World War 1: the 9th Reserve in Bramshott (Part 7)

World War 1: Taken on Strength… to France (Part 8)

Arleux-en-Gohelle (a.k.a Finding Max)

The Dominion British Cemetery (a.k.a. Finding Jack)