Much like places like Glasnevin and Colma, this is Bogotá’s city of the dead. There are more cemeteries in the city (e.g. Jaime Garzón is buried in the Jardines de la Paz; there is also an English Protestant Cemetery that is hidden) but this is the largest and it contains a number of Colombia’s historical personalities.

The cemetery has an inner circle and an outer circle. It *appears* as though the inner circle contains the older graves and those people of historical importance to Bogotá… it is only accessed through one entrance along Calle 26. The outer circle seems to house memorials and common graves and there are multiple entrances. There are so many graves that every single piece of space that can be utilized is; so, the single historical graves are surrounded by walls of vertical structures full of ashes or bodies.

Below you will find a random snapshot of people who are a part of Colombia’s volatile political history. One thing to note about Colombian naming: traditional Colombian society is matrilineal and naming follows the mother’s line rather than the father’s. So, in many of the graves, men have their given name, their father’s last name, and their mother’s last name on their stone (e.g. in the case of Santiago Pérez de Manosalbas, Pérez is his father’s family name and Manosalbas is his mother’s family name). Also, modern Colombian women are not required to take a man’s last name though the older graves will show a similar naming practice from the male line (e.g. in the case of Emelina Lemus de Tovar, Lemus is her father’s last name and Tovar is her husband’s).

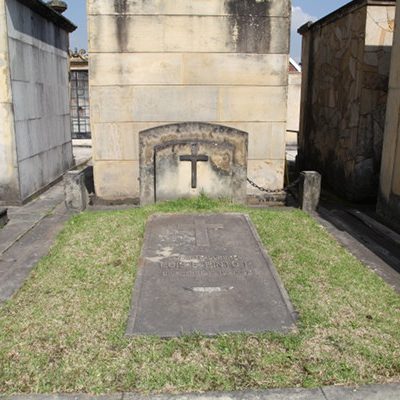

Santiago Perez de Manosalbas (1830-1900)

Santiago Pérez de Manosalbas (1830-1900) is responsible for much of the banking and public educational structure in Colombia. He spent his early life as foreign minister to multiple countries and partook in ousting of President Tomas Cipriano de Mosquera; Pérez later became president from 1874-1876. During his time in office, the Colombian Civil War of 1876 broke out… in part due to his educational policies. He believed in government-controlled public education while opponents believed in education controlled by the Catholic Church. He died in France while in exile. He was originally buried in Batignolles Cemetery in Paris but was repatriated to Bogotá in 1952.

Rafael Uribe Uribe (1859-1914)

Rafael Uribe Uribe (1859-1914) was a General in the Liberal Party Rebel Army and proponent of the British concept of Guild Socialism. He fought for the workers… particularly those in the coffee industry and was an active opponent to Regeneration, which advocates for the restriction of civil liberties. He was heavily involved in the Thousand Days’ War, a struggle between the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party over the belief that the Conservatives maintained governmental power through vote fixing. He was murdered on October 26, 1914 by two hired assassins using an ax.

Juan Bautista Tovar Morales (1862-1927)

Next to Uribe is Juan Bautista Tovar who was one of the key generals involved in the Thousand Days’ War. However, he is known for a different slice of Colombian history. When Simón Bolívar defeated the Spanish monarchy and led Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia to independence, he helped form a union of states known as Gran Colombia (1819-1831). When Gran Colombia was created, Panama was considered a part of Colombia. 84-years later in 1903, Panama pushed for independence with support and help from the United States. One of the Colombian Generals sent to Panama to quell the separatists was Juan Tovar. Upon arrival in Panama, he and his troops were separated and Tovar (sometimes Tobar) was put in jail until Panama could decide on whether or not to separate. Not much is in the historical record for Tovar after this; his headstone says he died in 1927.

José María Hernandez Vivas (1892-1933-ish)

Between September 1, 1932 – May 24, 1933, Colombia and Peru went to war in the small town of Leticia, which is at the point where Colombia, Peru, and Brazil all meet; the conflict was over the taxation of sugar. At this point, the military in Colombia was rather spotty and a large number of locals volunteered for service… José María Hernandez was one of these. A farmer and father he felt passionate about fighting to protect his homeland. During this short war, Hernandez was captured, tortured, and eventually executed. It’s said that during his execution he yelled out, Mi muerte le conviene a mi patria, Colombia sabrá vengarme. (My death is for/will suit my country, Colombia will know revenge.). This put Hernandez into the history books as a martyr. His memorial says Martir de la patria (Martyr of the country) and he is remembered fondly as a man of the people for his bravery.

Luis Francisco Pinto Parra (1908-1948)

Luis Francisco Pinto Parra (1908-1948), was a Colombian pilot who was responsible for much of South America’s defence strategy during World War II. While Colombia supported the Ally countries during the war, it did not send troops to the front. Instead, it defended South America from frequent German U-boat attacks. During this time, Pinto held many positions in the Air Force: Commander of the WW2 air bases in Buenaventura (dubbed Air Base of the Pacific) and Palanquero (Heavy Bombardment Squadron Base), General Aviation Head of Operations, Air Base Inspector General, and Director of the Military Aviation School. In 1946, he was appointed the position of Commander of the Colombian Air Force. He died while operating a commercial LANSA flight out of Bogotá, which exploded during takeoff. Luis Francisco Pinto Parra Air Force Base in Melgar is named after him. It’s likely that Pinto and President Gustavo Rojas Pinilla (1900-1975) knew each other because their careers followed the same path at roughly the same time.

Jose Raquel Mercado (1913-1976)

Most of the research for this post was done in Spanish. But, I was still surprised to discover that Jose Raquel Mercado (1913-1976) doesn’t appear on sites like Wikipedia; in fact, I could find nothing about Raquel in English. But he is remembered by Colombians… while I was by his grave, boys in uniform arrived with strings of flowers, which they wrapped around his bust. Raquel was el presidente de la Confederación de Trabajadores de Colombia (CTC). Essentially, the CTC is a workers union and Raquel was the boss. Jose’s body was found on April 19, 1976; he was kidnapped and killed by the Movimiento 19 de abril (abbreviated M-19), which was a guerrilla movement created in 1970 when Misael Pastrana Borrero was voted into power. The M-19 didn’t feel that Raquel was doing enough to support Colombian workers and ordered his assassination.

Carlos Pizarro Leongomez (1951-1990)

Less than a 100-metres away from Raquel is another grave covered in flowers, that of Carlos Pizarro Leongómez (1951-1990), the fourth in command of the M-19. Amongst other things, he and his compadres were responsible for the theft of Simón Bolívar’s sword, the same sword used by Bolívar to free Colombia and other Latin American nations from the Spanish Empire; this became a symbol of freedom for the M-19. The sword was later returned to Colombia as part of peace negotiations between guerrillas and the government. Pizarro was assassinated on 26 April during the 1990 elections, for which he was running for the presidency.

The Guard

Remember how in this post I mentioned that I had few problems in Bogotá. The Cementerio Central was one the exception to this rule. Overall the place was peaceful; there were lots of people visiting the graves of friends and relatives… young men came to add flowers to the graves of leaders, men kneeled and kissed Carlos Pizarro‘s grave and women were standing beside the grave of José Ignacio Lake Alvarez, a Colombian boy who reputedly drowned boy in Germany… they ask for favours. Outside the walls, people sold flowers, tchotchke and memorial stones. There’s an entire industry that revolves around sales for the cemetery.

Inside private security ride around the cemetery on bikes to *I originally supposed* make sure there’s no crime or grave desecration. However, I had an interesting run-in with one of the security guards. I meandered the cemetery doing my curiosity thing, taking photos, and periodically reading the stones. For some reason here, I wasn’t keen on pulling my camera out unless I was alone… the place felt weird and my camera stayed mostly in my bag.

As it happened, one security guard on a bike rode by, paused, looked at my stomach (where my money belt was), looked at my bag (where my camera was), and rode off without looking at my face. This made me suspicious so I aimed to be around at least one or two other people in my wanderings. Because I was judicious about pulling out my camera in the cemetery, for him to know about it meant he had been watching me.

About 10-minutes later, the same security guard came back and started asking me questions in Spanish… the first being “are you travelling alone.” Of course not. Never. My large husband has gone to get us water and will be right back. Then he asked to see my camera. To which, I replied that I don’t speak any Spanish and couldn’t understand what he was saying. I promptly thanked him for talking to me, his concern, for doing such a wonderful job, and attached myself to two women who were admiring the grave of Julio Garavito. The guard went away.

It would have been fine at this point, except later, in my attempts to find my way out of the cemetery from the outer circle, I stumbled upon him behind a wall grave stones smoking drugs… and he saw me.

This is when I became extremely grateful for all the “games” my brother and I played as kids in the woods… the ones where we avoided each other by hiding behind trees as “spies” and quietly made our way home without being seen. I played the exact same game as I moved between the confusing jumble of tightly packed graves towards one of the back entrances (where all the flower and tchotchke sellers were). The security guard frantically biked around in circles looking for me as I melted into the cemetery and eventually disappeared out into the city… like a quiet ghost.

I also became grateful for a second thing… a few blocks away, I stumbled upon pre-Colombian stones that I’d visited during a bike tour that I partook in the day before… and I knew exactly where I was in relation to the tourist areas. I also knew where there was a safe cafe and how far to go to get back to La Candelaria. After leaving the walls of the cemetery, I never saw the guard again.

0 comments on “Cementerio Central de Bogotá”Add yours →