It might surprise you to know that the creator of Cthulhu and Arkham, friend to Houdini, Derleth, Wandrei, Ashton Smith, Bloch, Kuttner, Howard and Loveman, and the inspiration to countless writers, artists, musicians, and filmmakers was not well known and mostly out of print by the time of his death in 1937.

He’s now considered one of the most significant 20th-century authors and the person who spawned an entire genera of fiction: cosmic horror. But, Howard Phillips Lovecraft died penniless, destitute, and reliant on the kindness of relatives.

For the first part of his life, Lovecraft was a recluse who rarely left Rhode Island. It was only after his mother was committed to an institution in 1919 that he began to venture away from his home.

Boston was a common destination and he frequently travelled to the city to see lectures and visit friends. Lovecraft wrote in a letter to Lillian D. Clark (his maternal aunt nee Lillian Delora Phillips) that it was during a 1927 tour of Massachusetts with Donald Wandrei that the two visited the sites that inspired Pickman’s Model.

This means that the story was wrapped around real places and not in a fictional world that he created in his head. This is the only Lovecraft story to be exclusively set in Boston and below are some of the locations that are seen in the tale.

The Story

Pickman’s Model is narrated by Thurber, the friend of a Boston artist named Richard Upton Pickman. Throughout the story, Thurber relates to an acquaintance named Eliot an experience that he had with Pickman just before the artist disappeared.

If you’re not familiar with the story, you can listen to it on YouTube or read it at hplovecraft.com. The original publish date for the story was 1927 though it was written and set in 1926.

It all starts with… “Boston never had a greater painter than Richard Upton Pickman.”

The Setting

“The place for an artist to live is the North End. If any aesthete were sincere, he’d put up with the slums for the sake of the massed traditions. God, man! Don’t you realize that places like that weren’t merely made, but actually grew? Generation after generation lived and felt and died there, and in days when people weren’t afraid to live and feel and die.”

The North End is the oldest residential neighbourhood in Boston. It was settled in the 1630s by the descendants of the Puritan families who settled in New England. Originally an affluent Boston community, many of the residents were still loyal to England when the first shots of the American Revolution were fired.

When the dust settled, one-third of the population of Boston left the city and the demographics of the North End abruptly changed. Those who were left behind vacated the North End for Beacon Hill and the buildings quickly filled with new sets of immigrants: Irish, Italian, and Eastern European.

The North End in the 1920s (Lovecraft’s era) was in a dire situation. It was a rundown, deteriorating, overcrowded community full of people crammed together in tenement buildings. It was a place where immigrant families could buy cheap housing. It was also a place where artists could rent studios for pennies.

This is reflected when Lovecraft writes, “I took it because of the queer old brick well in the cellar—one of the sort I told you about. The shack’s almost tumbling down, so that nobody else would live there, and I’d hate to tell you how little I pay for it.”

This is in stark contrast to the Victorian community of Back Bay, which was created after the failure of an expensive milldam project designed to connect Boston to Watertown. Instead, the city filled the Bay with dirt and created new residential land.

“You know,” he said, “there are things that won’t do for Newbury Street—things that are out of place here, and that can’t be conceived here, anyhow. It’s my business to catch the overtones of the soul, and you won’t find those in a parvenu set of artificial streets on made land. Back Bay isn’t Boston—it isn’t anything yet, because it’s had no time to pick up memories and attract local spirits.”

Newbury Street runs through the Back Bay community and in the 1920’s it was considered “the” fashionable place to live in Boston. Even today the streets are lined with high-end retail shops and galleries.

When Lovecraft writes, “They were his pictures, you know—the ones he couldn’t paint or even shew in Newbury Street…” he is likely referring to showing the paintings at the Guild of Boston Artists (162 Newbury Street). In the 1920s, this was the only gallery along the street and it was run by a group of prominent Boston artists.

Of course, there were other galleries in the city but they didn’t emerge on Newbury until after Lovecraft’s death. In 1957, the CoSo in the photo above (Copley Society of Art) was one of the galleries to appear on the street; this gallery started in the 1880s as a Victorian spinoff from the Museum of Fine Arts (also mentioned in the short story).

The Studio

So, let’s talk a little bit about the location of Pickman’s studio…

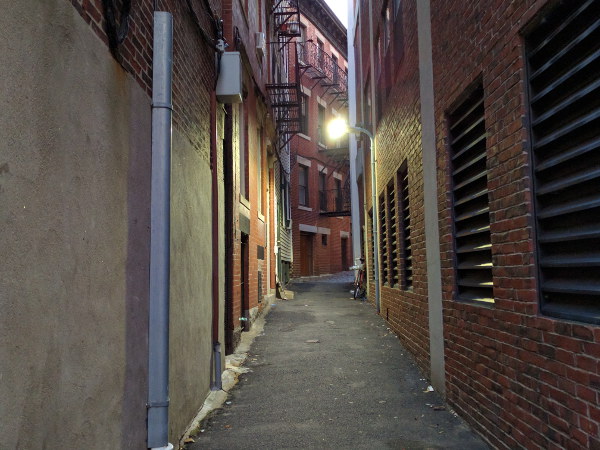

“When we did turn, it was to climb through the deserted length of the oldest and dirtiest alley I ever saw in my life, with crumbling-looking gables, broken small-paned windows, and archaic chimneys that stood out half-disintegrated against the moonlit sky… we turned to the left into an equally silent and still narrower alley with no light at all, and in a minute made what I think was an obtuse-angled bend toward the right in the dark. Not long after this Pickman produced a flashlight and revealed an antediluvian ten-panelled door that looked damnably worm-eaten.”

The alleys in the North End are both chaotic and lovely at the same time. While I stood staring into one, a passerby commented, “they really are amazing aren’t they?”

But, the alley and old building that inspired Lovecraft no longer exists. It did at one point because he comments about it in his personal letters, but it was gone by the time he and Donald Wandrei visited in 1927.

The North End of Boston underwent a huge infrastructure makeover in the early part of the 20th century. This uncovered a whole mess of hidden buildings, tunnels, and problems that the city was not ready to fully acknowledge.

“There’s hardly a month that you don’t read of workmen finding bricked-up arches and wells leading nowhere in this or that old place as it comes down—you could see one near Henchman Street from the elevated last year.”

Yes… during the construction city workers did find what the people of Boston affectionately refer to as Captain Gruchy’s tunnels.

“Look here, do you know the whole North End once had a set of tunnels that kept certain people in touch with each other’s houses, and the burying-ground, and the sea?”

But these tunnels are much older than Captain Gruchy and most of the buildings and streets that now stand in the North End.

I talked with one historian from the Christ Church who said that there is a tunnel that runs from the old Dodd estate to what is now the intersection of Henchman and Commercial Streets. It was the end of this tunnel that the city discovered in the clipping above. This tunnel was already well established by the time Gruchy discovered it, and runs diagonal to the buildings and streets.

The “Dodd House” you see now across the street from the Old North Church, is not actually the Dodd House. The real manor is up the hill at 190 Salem Street and was built in 1804. There is an older bricked up tunnel in the basement. I talked to the woman who owns the house; she confirmed its existence.

The thing that the city originally didn’t want to deal with in the early 1900s was the presence of tenement buildings crammed into the middle of city blocks; they were not accessible by streets and could only be accessed via tiny alleys and tunnels that ran under buildings.

The black areas in the map below depict “residential only” buildings (and not buildings with storefronts). As you can see, some have no street-side entrance.

But, by the 1920s, something needed to be done because not only did these pose a fire hazard to residents but they were also identified as a means in which disease and crime could flourish. The city reasoned that because there were no open spaces for people to move around and for children to play that the residents were unhealthier. Here is a copy of The North End, a Survey and a Comprehensive Plan by the City of Boston 1919 (PDF format).

While entire sections of the North End were not removed like planned (it was too costly), many older buildings within the blocks were removed to make space for greenery. This may be what happened to Pickman’s studio and why Lovecraft wrote in a letter to Lillian D. Clark “the actual alley & house of the tale utterly demolished, a whole crooked line of buildings having been torn down.”

I walked this area extensively and followed the path laid out by Lovecraft; both the path in…

“We changed to the elevated at the South Station, and at about twelve o’clock had climbed down the steps at Battery Street and struck along the old waterfront past Constitution Wharf. I didn’t keep track of the cross streets, and can’t tell you yet which it was we turned up, but I know it wasn’t Greenough Lane.”

…and the path out:

“He led me out of that tangle of alleys in another direction, it seems, for when we sighted a lamp-post we were in a half-familiar street with monotonous rows of mingled tenement blocks and old houses. Charter Street, it turned out to be, but I was too flustered to notice just where we hit it. We were too late for the elevated and walked back downtown through Hanover Street. I remember that wall. We switched from Tremont up Beacon, and Pickman left me at the corner of Joy, where I turned off.”

I ferreted out two areas that seem the most likely candidates for the location of Pickman’s studio.

The first possible location for Pickman’s studio was in the block between Henchman, Hanover, Charter, and Commercial (previously known as Lynn Street). The narrator says he knows “it wasn’t Greenough Lane” but the alley that runs through the block (named Greenough Lane) was the longest, the most complex, and follows the obtuse path laid out by Lovecraft.

The modern green space in the middle (now Charter Street Park) is big enough to easily hold a row of buildings; and, city records show that the area once contained clapboard houses dating to the 1800s (one still exists because of its historical significance). The only way to access these houses was via the alley.

Here is how the alley looked in 1891:

The second candidate for Pickman’s studio is the block between Henchman, Foster, Charter, and Commercial. This is the only other long alley that runs to buildings in the middle of a block in the area Lovecraft describes.

The alley that shows on the map is now a massive parking lot and the block of Victorian buildings that surround the block has been slightly refactored.

According to historical MACRIS records, the remaining buildings date to the 1890s so they wouldn’t have been missing during Lovecraft’s visit with Wandrei. It’s likely that whatever was in the middle was simply scooped out, which matches Lovecraft’s “whole crooked line of buildings having been torn down” description of his visit in 1927.

The endpoint for the alley that shows on the map above ends at what is currently Goodridge Alley. You can still access the alley from Charter Street but it now takes you to an enclosed courtyard.

Given all this information and Lovecraft’s description in both the short story and in his letters, I’m leaning towards the second candidate (a lane off Foster) as being the location of Pickman’s studio.

I followed Thurber and Pickman’s walk back to the Boston Common via Charter –> Hanover –> Tremont –> Beacon and the corner of Joy. Joy runs through Beacon Hill and in the other direction is the Boston Common. There’s nothing to report from this walk other than it took roughly 30-minutes.

The Characters

Richard Upton Pickman

Lovecraft tells you exactly who and what Richard Upton Pickman is: a changeling.

“I suppose—you know the old myth about how the weird people leave their spawn in cradles in exchange for the human babes they steal. Pickman was shewing what happens to those stolen babes—how they grow up—and then I began to see a hideous relationship in the faces of the human and non-human figures… And no sooner had I wondered what he made of their own young as left with mankind in the form of changelings, than my eye caught a picture embodying that very thought… It was that of an ancient Puritan interior—a heavily beamed room with lattice windows, a settle, and clumsy seventeenth-century furniture, with the family sitting about while the father read from the Scriptures. Every face but one shewed nobility and reverence, but that one reflected the mockery of the pit. It was that of a young man in years, and no doubt belonged to a supposed son of that pious father, but in essence it was the kin of the unclean things. It was their changeling—and in a spirit of supreme irony Pickman had given the features a very perceptible resemblance to his own.”

This isn’t the only time we see Pickman in a Lovecraft tale. He also appears in The Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath in his monster form.

“There, on a tombstone of 1768 stolen from the Granary Burying Ground in Boston, sat the ghoul which was once the artist Richard Upton Pickman. It was naked and rubbery, and had acquired so much of the ghoulish physiognomy that its human origin was already obscure.” – From The Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath.

Cotton Mather

While not a primary character in Pickman’s Model, Cotton Mather is mentioned three times while Thurber is setting the scene.

“You call the Salem witchcraft a delusion, but I’ll wager my four-times-great-grandmother could have told you things. They hanged her on Gallows Hill, with Cotton Mather looking sanctimoniously on.”

Cotton Mather was a prominent Puritan minister, Harvard graduate, and author of over 450 influential books and pamphlets, some of which helped fuel the trials. His tomb is located on Copp’s Hill.

There are four trials that Cotton Mather was involved in and four women that he writes about in Wonders of the Invisible World: Bridget Bishop, Susanna Martin, Elizabeth How, and Martha Carrier. All were convicted of witchcraft and all were hung on Gallows Hill.

Sadly, of Susanna Martin, Mather writes she “was one of the most Impudent, Scurrilous, wicked creatures in the world…” This sort of testimony coming from a highly political and influential minster and academic can only mean the death sentence for a Puritan widow.

By the 1920s, the witch trials were old news in Boston and most of these women had been exonerated and the families compensated for their losses.

When Lovecraft writes, “Mather, damn him, was afraid somebody might succeed in kicking free of this accursed cage of monotony…” he is referring to the understanding that the witch trials had nothing to do with witchcraft at all; but rather, was a persecution of free thinking, successful, and independent women. The vast majority of these women were landholders (through inheritance of the death of a spouse) and all had descendants who went on to do remarkable things.

The Paintings

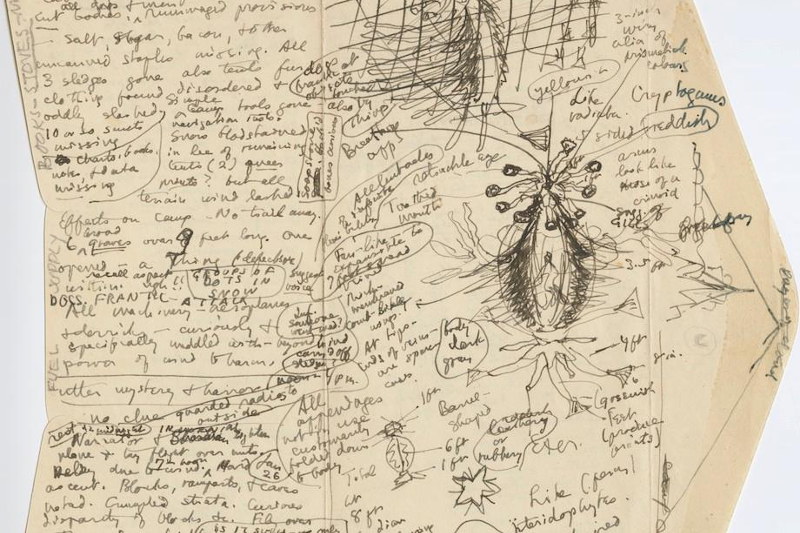

The paintings in Pickman’s Model take on a life of their own. They are like descriptive windows that give us glimpses of the grand mythos that Lovecraft created.

“The backgrounds were mostly old churchyards, deep woods, cliffs by the sea, brick tunnels, ancient panelled rooms, or simple vaults of masonry. Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, which could not be many blocks away from this very house, was a favourite scene.”

Copp’s Hill is iconic and packed with tourists daily. And, it is sufficiently archaic and creepy enough to be the backdrop to any horror painting or story. Here you’ll find plenty of the macabre New England winged skull headstones.

The oldest burials in the cemetery are of the Copp children and date to 1661.

Copp’s Hill hasn’t changed much over the centuries, which means it looks exactly the same as it did when Lovecraft visited and was inspired by the rows of crooked tombstones and scrubby grass.

Subway Accident

“Gad, how that man could paint! There was a study called “Subway Accident”, in which a flock of the vile things were clambering up from some unknown catacomb through a crack in the floor of the Boylston Street subway and attacking a crowd of people on the platform.”

This “crack in the floor of the Boylston Street subway” had me stumped me for a long time because many of the Lovecraft texts on the interwebs have this written as the “Boston Street Subway.”

But alas, there is no Boston Street in Boston; there is a Boston Street in Newtownville, and their electric above ground trolley system once ran along Boston Street (established in 1892); but, for the purposes of tracking down Lovecraft locations in Boston, the subway is on Boylston Street at the SE corner of the Boston Commons (at Boylston and Tremont).

Boston’s subway is sufficiently dark, dank, loud, and smelly… the perfect place for ghouls and mythical creatures. It was the first subway in the U.S. and the Tremont Street Subway was its inaugural line. This eventually became the city’s green line.

The Ghoul Feeding

“…my admiration for him kept growing; for that “Ghoul Feeding” was a tremendous achievement. As you know, the club wouldn’t exhibit it, and the Museum of Fine Arts wouldn’t accept it as a gift; and I can add that nobody would buy it, so Pickman had it right in his house till he went.”

The Museum of Fine Arts opened its doors on July 4, 1876, in celebration of the US Centennial. In 1909 the Museum moved to Huntington Avenue and has been there ever since. It’s unknown if Lovecraft visited it during one of his trips to the city.

When describing Pickman’s paintings, Lovecraft gives a shout out to some of his favourite artists.

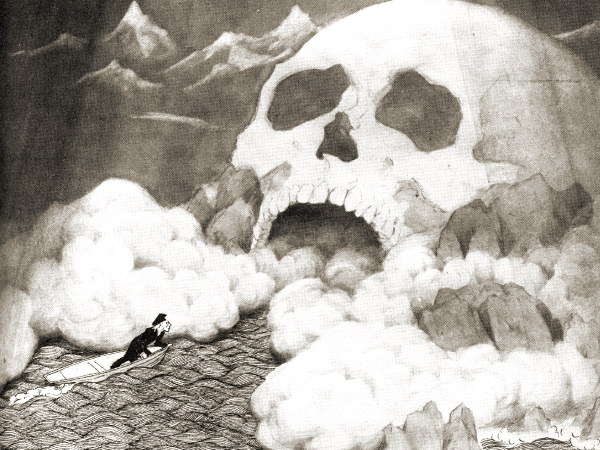

“There’s something those fellows catch—beyond life—that they’re able to make us catch for a second. Doré had it. Sime has it. Angarola of Chicago has it. And Pickman had it as no man ever had it before or—I hope to heaven—ever will again… [but]… There was none of the exotic technique you see in Sidney Sime, none of the trans-Saturnian landscapes and lunar fungi that Clark Ashton Smith uses to freeze the blood.”

Lovecraft seemed to prefer the detailed work of black and white illustrators to that of painters. None of these artists have work in the Museum of Fine Arts; perhaps because traditionally those in the fine art community tend to look down on the work of illustrators.

Like Gustave Doré whose fantastical illustrations often adorned The Bible, Shakespeare’s works, Dante’s Inferno, and poetry like the Rime of the Ancient Mariner. His final set of engravings were for Edgar Allen Poe’s The Raven. A portrait of him by Frederick Juengling is held at the Museum of Fine Arts but is currently not on display.

And, Sidney Sime whose work was dramatic, dark, and brooding but always included some element of satire or absurdity.

To give a shout out to Clark Ashton Smith was to acknowledge a friend and fellow writer. Smith was also an illustrator who brought life many different fantastical characters.

Anthony Angarola was both a painter and an illustrator. It’s noted that after his artistic success in The Kingdom of Evil that Angarola expressed interest in illustrating Lovecraft’s work. But, Angarola died before this could come to fruition.

Lovecraft and Boston

Lovecraft was very much a man born out of time. And, it seems only natural that he’d be attracted and fascinated by a place like the North End of Boston, which is also out of time with mysteries long forgotten or ignored by its residents. It’s dark, mysterious, complex, and layered streets hold a history that is rarely found elsewhere in the United States.

“There are secrets, you know, which might have come down from old Salem times, and Cotton Mather tells even stranger things.”

Great thread. When did you write this?

Thank you! It was published on Sep 29, 2016. It took a week to write. It’s been a while since I’ve been in Boston. Would love to spend time in Providence and dig into other aspects of Lovecraft’s world.

A wonderful piece of work; fascinating, labyrinthine, in spirit anyway, showing a healthy respect for morbid thoughts and feelings; and yet not in itself unwholesome or off-putting. H.P. Lovecraft was a romantic when it came to underground places, whether alleys, crypts or trolleys.

Thank you for sharing, Charlene,

John