This odd-shaped building in Edmonston (not to be confused with Edmonton) makes for a quick roadside attraction on your way through the Maritimes… or a quick rest stop in Canada before you cross the border into the U.S. at Madawaska.

Fortin du Petit-Sault was built in 1841 on a rocky outcrop where the Madawaska and the St. John River meet; in military terminology, this is known as a Blockhouse. A blockhouse is a single building with one room and multiple loopholes designed to shoot in all directions. From its perch on a rocky outcrop, the Blockhouse has an excellent view of the Edmonston area, which was exactly its original purpose.

This fort is the byproduct of a decades-long border dispute between the U.S. and the British Colonies… one that makes for a typical Canadian story that involves comical names, roll-your-eyes stories, and multiple border fortifications: Fort Ingall, Fortin du Petit-Sault, Seal Island, Hancock Barracks, Woodstock Blockhouse, and probably many more that have disappeared into the mists of time.

The Treaty of Paris

At the end of the American Revolution War and with the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1783), the definition of the location of the Canadian/American border and the rights of people on either side was both poetic and vague.

And that all disputes which might arise in future on the subject of the boundaries of the said United States may be prevented, it is hereby agreed and declared, that the following are and shall be their boundaries, viz.; from the northwest angle of Nova Scotia, viz., that angle which is formed by a line drawn due north from the source of St. Croix River to the highlands; along the said highlands which divide those rivers that empty themselves into the river St. Lawrence, from those which fall into the Atlantic Ocean, to the northwesternmost head of Connecticut River; thence down along the middle of that river to the forty-fifth degree of north latitude… – From Article 2 of the Treaty of Paris.

To make matters vaguer, certain provisions were written into the treaty that caused territorial conflict.

…the inhabitants of the United States shall have liberty to take fish of every kind on such part of the coast of Newfoundland as British fishermen shall use, (but not to dry or cure the same on that island) and also on the coasts, bays and creeks of all other of his Brittanic Majesty’s dominions in America; and that the American fishermen shall have liberty to dry and cure fish in any of the unsettled bays, harbors, and creeks of Nova Scotia, Magdalen Islands, and Labrador, so long as the same shall remain unsettled, but so soon as the same or either of them shall be settled, it shall not be lawful for the said fishermen to dry or cure fish at such settlement without a previous agreement for that purpose with the inhabitants, proprietors, or possessors of the ground. – From Article 5 of the Treaty of Paris.

This article led to both countries rushing to map, settle, and catalogue (census and vital records) the vague areas (pretty much the entire border of Canada/US). There was a renewed push to bring settlers from Europe (like in this post), only hindered by the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812.

The Treaty of Ghent

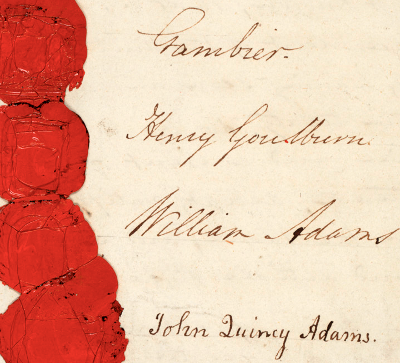

At the end of the War of 1812 and with the Treaty of Ghent (1814), more confusion ensued with the new treaty, which glossed over the land and property claim disputes (and threw in some lame concessions for Aboriginal Peoples and a half-hearted attempt to abolish slavery).

All hostilities both by sea and land shall cease as soon as this Treaty shall have been ratified by both parties as hereinafter mentioned. All territory, places, and possessions whatsoever taken by either party from the other during the war, or which may be taken after the signing of this Treaty, excepting only the Islands hereinafter mentioned, shall be restored without delay and without causing any destruction or carrying away any of the Artillery or other public property originally captured in the said forts or places, and which shall remain therein upon the Exchange of the Ratifications of this Treaty, or any Slaves or other private property; And all Archives, Records, Deeds, and Papers, either of a public nature or belonging to private persons, which in the course of the war may have fallen into the hands of the Officers of either party, shall be, as far as may be practicable, forthwith restored and delivered to the proper authorities and persons to whom they respectively belong.

Essentially, nothing changed. The treaty was a slap on the wrist with a hearty you should know better, after which both parties were sent back to their respective corners to lick their wounds and eat crow.

Lands that had been fought over were returned, fishing rights were still confusing, the boundaries were still vague, and both sides agreed that a commissioner should be appointed to resolve territorial disputes.

The confusion was further acerbated when Maine separated from Massachusetts and both states began selling lumber from the disputed areas (often stepping on each other’s toes).

Britain still considered most of Maine to be British territory (because of the lumber) and took steps to protect all routes in and out. In the West, they faced similar challenges with 54° 40′ or Fight (a.k.a. the Oregon boundary dispute).

When “two Commissioners” were sent to the region to resolve land claim issues (as was defined in the Treaty of Ghent), it’s said that locals got the commissioners so drunk that they surveyed the wrong area and were unable to resolve any claims. This isn’t the first time this has happened; Fort Blunder is a great example of a drunken surveying mistake.

All these territorial disputes would eventually lead to skirmishes in the Edmonston area, which were blown out of proportion when one man (John Baker) attempted to create a filibuster republic (in foreign policy terms; not government stalling terms) in New Brunswick.

As the story goes, John Baker planted a handmade flag on the New Brunswick side of the St. John River, declared the area the free Republic of Madawaska (1827) with a handful of American families and Les Brayons who had already settled the area. He then proceeded to build a gristmill and sawmill in what is now known as Baker Brook, New Brunswick.

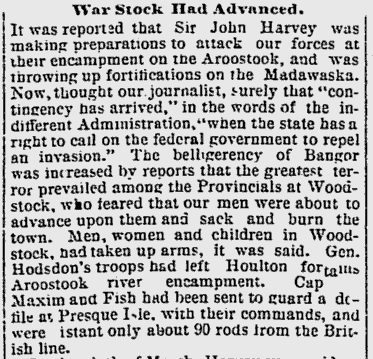

For his brazen actions, Baker was promptly arrested by the British, put in jail, tried for conspiracy, convicted, and fined. This angered the American government and they sent three companies of the 1st Artillery Regiment to man the Hancock Barracks in Houlton, Maine (nowhere near the Republic of Madawaska).

The British responded by building a Blockhouse across the river in Woodstock, New Brunswick. The two forts became a frequent holding place for any lumberjack, surveyor, census representatives, or pedestrian who happened to be wandering in the woods during this period (e.g. Ebenezer Greeley).

This may sound rather intense, but in reality, the troops at these two forts were very friendly with each other. After all, part of the world is known for its brutally cold winters, dark evenings, and boring woods… and most of these men were related to each other regardless of what side of the “border” they came from.

Pork and Beans War

The Pork and Beans War (a.k.a. the Aroostook Bloodless War) could have easily been the inspiration for the movie Canadian Bacon because (like in the movie) there was no actual war… just a disagreement about the official location of the border between Canada and the US.

I’d like to think that the Port and Beans war got its name because that’s what the soldiers (read: lumberjacks, Canadian militiamen, British regulars, settlers, and American regulars) did during this skirmish… sat around in the woods, gossiped about the people in their life, and ate American canned pork and beans on a campfire while waiting for direction from absent politicians.

Even though labelled a “bloodless war,” 38-men died (from the cold, training accidents, friendly fire, and disease), there were frequent arrests and lots of chest-thumping with sabre-rattling. The press had a field day because this is the most exciting thing that happened for years.

In one story, an American posse caught Canadian Lumberjacks cutting down trees on the unoccupied land of William Eaton. The two groups started to fight but were interrupted when a black bear that was somehow not in hibernation in January attacked the group.

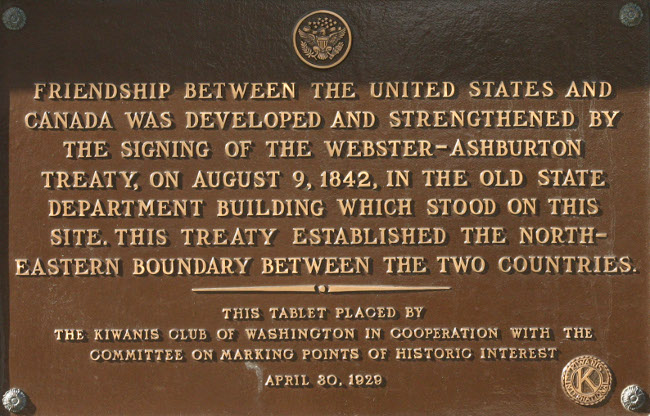

The Pork and Beans War ended in 1842 with the precise and detailed Ashburton-Webster Treaty. Incidentally, the British were feeling particularly generous during the negotiations and also ceded the land with Fort Blunder to the Americans.

So, what happened to Fortin du Petit-Sault? The original fort was built towards the war, just before the signing of the Ashburton-Webster Treaty. And, true to its temporary nature and high location, the original fort was hit by lightning in 1855 and destroyed. The existing fort was built in 2000.

0 comments on “Whose Fort is this Fort? The story behind Fortin du Petit-Sault”Add yours →