While the steeple at the Christ Church in Boston has fallen and been replaced a couple of times during its 272-year history, the bells are original. Each of the eight “maiden peel” bells date to 1744 and weigh roughly between 600-1500 lbs each.

Remember Timothy Cutler from the previous post? He was the man who determined the church needed bells and requested they be cast by Rudhalls of Gloucester; bell number 6 has the following inscription, “We are the first ring of bells cast for the British Empire in North America, A.R. 1744.” They weren’t actually installed in the bell tower until 1745/6.

To install, workers had to remove the steeple, haul the bells up the side of the church, hang the bells in the tower, and put the steeple back on; to give you a sense of placement, the bell ringing chamber is behind the plaque in the photo below, and the bells are behind the arched window (near the top of the brick).

Once the dust had settled and the bells were insured, shipped, and installed, there wasn’t enough money left in the church’s coffers to hire change ringers so they sat silent until 1750.

It was in that year that a group of boys approached Cutler to ask if they could work as the church’s bell ringers for two pennies a week. And, to make sure they would get paid, the boys drew up a contract. The second name on the contract is Paul Revere.

The bells are “change ringing bells,” meaning that each bell does a full circle as part of one ring… a full cycle of all 8-bells is called a “round” and the round must be complete before each bell is rung again. In an hour, it’s typical to do about a thousand different round combinations.

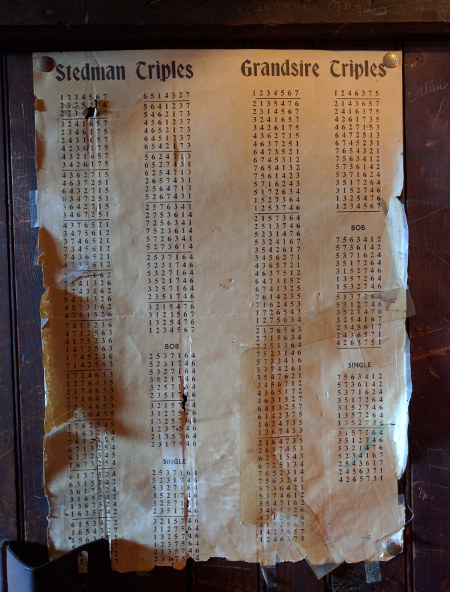

The order in which each numbered bell rings varies and is memorized by the group and coordinated by a lead (e.g. 2,1,3,5,4,7,5). Below are some musical patterns used in this church.

The bells don’t have names (like the bells in St. Andrew’s Church in Cambridge) but they are identified by their number and their note. All are treble bells except Bell Eight, which is a tenor.

>> Bell One: F (614 lbs)

>> Bell Two: E (616 lbs)

>> Bell Three: D (700 lbs)

>> Bell Four: C (812 lbs)

>> Bell Five: B flat (830 lbs)

>> Bell Six: A (945 lbs)

>> Bell Seven: D (1194 lbs)

>> Bell Eight: F (1536 lbs)

The Restoration of 1844

The bells have been restored a few times over the centuries; firstly in 1844, a hundred years after their creation. The only record of this comes from the recollections of a young boy (and later a bell ringer) named Arthur Nichols who visited the churchyard where the bells were stored during their restoration.

Unfortunately, at this time the bells were rehung without the proper change ringing apparatus because there was no one in the United States who understood change ringing. So, for decades the bells were merely chimed. Prior to this, there is no record (other than the contract signed by Paul Revere) that the bells were change rung.

The Restoration of 1894

The next restoration happened in 1894 and was funded by the same boy who first saw the bells in 1844: Arthur Nichols. When the bells were inspected and it was quickly determined that they’d been improperly hung and Nichols set out to make things right.

He hired a company to reinstall the bells and inspected the work himself; and, while the proper mechanisms were added, the work was shoddy and within 20-years the mechanisms had deteriorated significantly. It was determined during the work that the mechanisms used in 1744 were far superior to those available in 1894.

After this, bell-ringing became unfashionable in the United States and the bells stood idle for many decades. In 1925 the bells were tied into a fixed position and only rung by striking the clapper against the side of the bell. Over time, the jarring vibrations from this damaged the tower.

Tower Reinforcement in 1974

It wasn’t until 1974 that the bells were freed to test the integrity of both the bells and the tower in preparation for the American bicentennial and anniversary of Paul Revere’s historic ride. The goal was to use the bells as they were intended (as change ringing bells) for the ceremonies.

Engineers started with freeing one bell and from this determined that the tower would topple without structural changes.

As mentioned above, the tower had suffered years of damage from improper ringing because instead of swinging the bells in a full circle like they were meant to do, ringers simply yanked the clappers to the side of the bell and the jarring vibrations damaged the tower.

The entire thing was reinforced with steel before all eight of the bells could ring together as part of a change ringing round.

By the 1970s, beyond a few brief pockets of time, the bells were rarely used as change ringing bells. When the one freed bell rang, the secretary to the vicar (Dorthy Larson) was quoted saying, “It didn’t sound like the regular peal of the bells I’m used to. I heard the bell going for a long time — deep and resonant and beautiful.”

The Restoration of 1983

In 1983, the bells were completely removed from the tower (carefully without taking off the steeple) and sent to the Museum of Science for cleaning and restoration; and, while they were away, the frames and fittings in the church were replaced.

The elm headstocks on which the bells were mounted were replaced with steel heads cast in the Whitehall Foundry. And, for the first time since their creation, a bell hanger from the Whitechapel Hall foundry travelled to Boston to do the work.

They were remounted in time for the 200-year celebration of the Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution and signalled a truce between the UK and the United States.

It was in 1974 that for the first time in the city’s history change ringing/campanology was offered as a course at MIT, which has continued until the present day.

These days change ringing is regularly heard every Sunday at Christ Church as professors and students carry on the tradition.

0 comments on “These bells didn’t really sing until the 20th century”Add yours →