This is the seventh post in a series about a group of World War 1 soldiers from Mill Village, Nova Scotia who all enlisted for the 209th Battalion in Swift Current, Saskatchewan. For full context and more information about the people below, Part 1 is here. There is also a remembrance page with links to all the posts in this series, which can be found here.

The Creation of the 9th Reserve Battalion

In January 1917, as part of a larger restructuring, the CEF Canadian battalions in England were absorbed or morphed into 26 new reserve battalions. These would become the reserve battalions that would feed the units fighting in France.

And, this is when things get a bit confusing for the Mill Village / Cabri men.

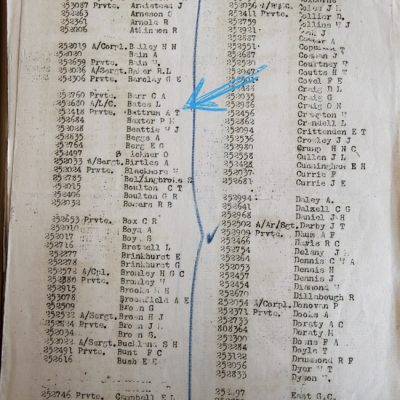

The 9th Reserve was created in Bramshott on January 4th, 1917, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Armstrong. This new Battalion initially absorbed the 9th, 194th and 209th Battalions (even though technically the 209th had already been absorbed by the 9th). The 202nd Battalion was added in May 1917.

The Cabri/Mill Village men were attached to the “B” Company of the 9th Reserve. There was nothing new in the “B Company” designation except that Archie was no longer with the other men; on the same day that Max was admitted to the hospital at Shorncliffe (December 14, 1916), Archie was deemed “Category A02 Fit” meaning he was ready for service. He moved from the “B” Company to the “A” Company and prepared for overseas service.

However, on January 4, 1917, the “9th Battalion” was absorbed into the “9th Reserve” Battalion, all of our men were put into the “B Company” (including Archie), and were moved 150km inland to Bramshott, a temporary Canadian base in Southern England near Liphook (roughly halfway between London and Brighton). No one headed overseas.

Bramshott

Like Shorncliffe, life in Bramshot was damp and wet. In the winter of 1916, England experienced an abnormally large amount of snow and rainfall. This can’t have been good for the soldiers who were living in tents, and like already seen, many became sick. Complaints were sent back to the Canadian Government and officials visited the camp to negotiate better conditions for the soldiers.

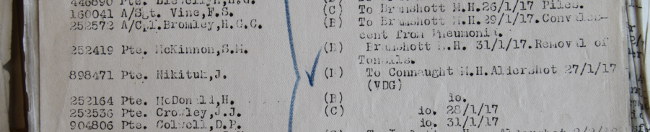

A month after release for rubella, Max was re-admitted to the hospital suffering from tonsillitis (January 31).

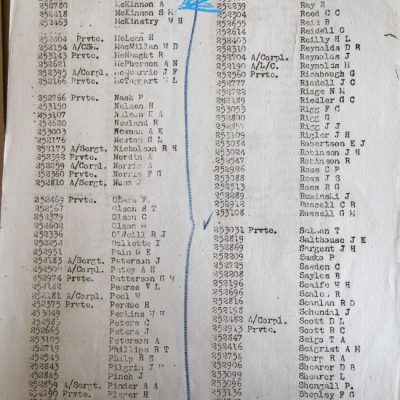

Records from the National Archives of Canada. Photos taken by Sharlene McKinnon.

Records from the National Archives of Canada. Photos taken by Sharlene McKinnon.

According to the medical report, Max “gives a history of having an attack every few weeks and wants his tonsils removed.” They were removed two days later; tonsil removal was an extremely common surgery among the men.

Photo of an operation at Bramshott from the National Archives of Canada.

Photo of an operation at Bramshott from the National Archives of Canada.

Max spent a total of 14-days in the hospital. He was cleared for active duty on Feb 13, 1917.

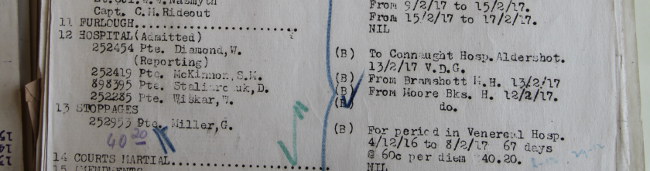

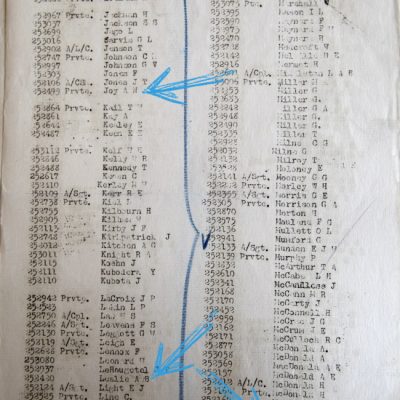

Not long after Max’s surgery, Arthur Joy made an appearance in the Battalion medical records but at a different hospital: the Connaught Hospital in Aldershot.

Record from the National Archives of Canada. Photos taken by Sharlene McKinnon.

Record from the National Archives of Canada. Photos taken by Sharlene McKinnon.

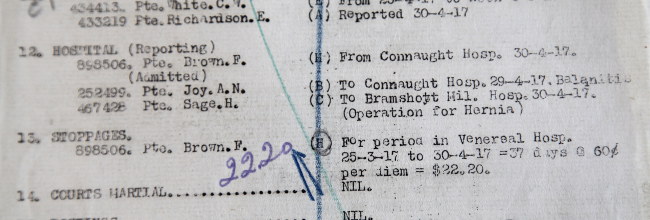

He was suffering from both “balanitis” and “traumatic orchitis” due to venereal disease; he’s noted in his records to have “VDG” (venereal disease gonorrhea), which keeps him bedridden for months. The cure for VD did not come until the discovery of penicillin and widespread use in the 1930s.

Record from the National Archives of Canada. Photos taken by Sharlene McKinnon.

Record from the National Archives of Canada. Photos taken by Sharlene McKinnon.

Men who suffered from VD were separated from the other sick and wounded and docked pay (by 40%) until they were ready for active service. This was a costly disease for the military and for Arthur it would keep him in the hospital for most of the war (when combined with other secondary diseases).

Life in the 9th Reserve

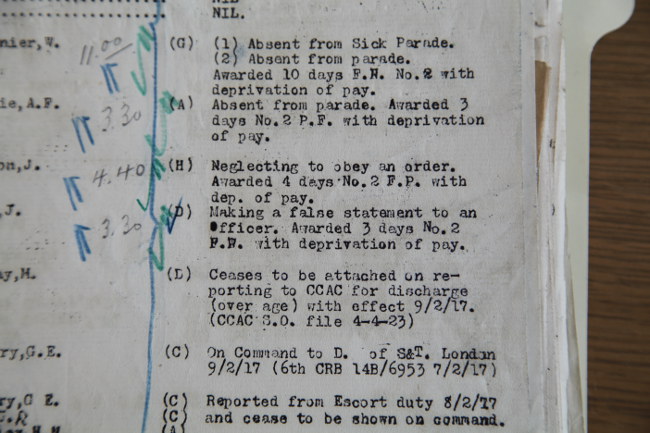

Nearly every Daily Report had some sort of “drama” reported. Men getting drunk. Failure to salute officers. Soldiers absent from the daily Tattoo or some parade (sick, pay, bath). Soldiers making false statements. Murder. Assault. Insubordination.

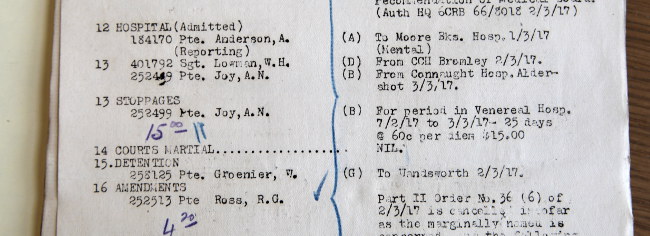

Record from the National Archives of Canada. Photos taken by Sharlene McKinnon.

Record from the National Archives of Canada. Photos taken by Sharlene McKinnon.

For each issue, men were docked pay and detained for a period. With some soldiers (e.g. Robert Cairns or William Hughes), their name keeps appearing on page-after-page in the Daily Report. Robert Cairns always seemed to be in trouble… so they’d send him overseas. Then shortly after, he’d return with some sort of injury. This continued throughout the war until demobilization.

Our men never appear in the punishment roll. In fact, it was rather rare to see a 209th Battalion regimental number on any of the lists. They quietly spent their time training, parading, and waiting.

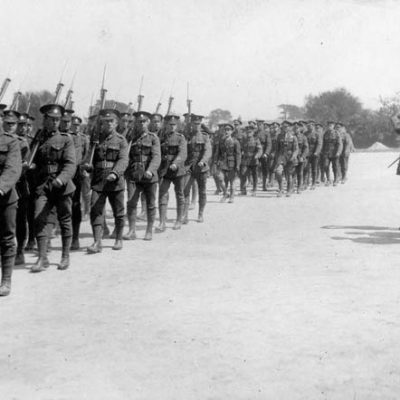

The new arrivals were given the Enfield Rifle, which replaced the fickle Ross Rifle, so they needed to be trained in its use. They continued to practice their hand to hand combat and trench tactics.

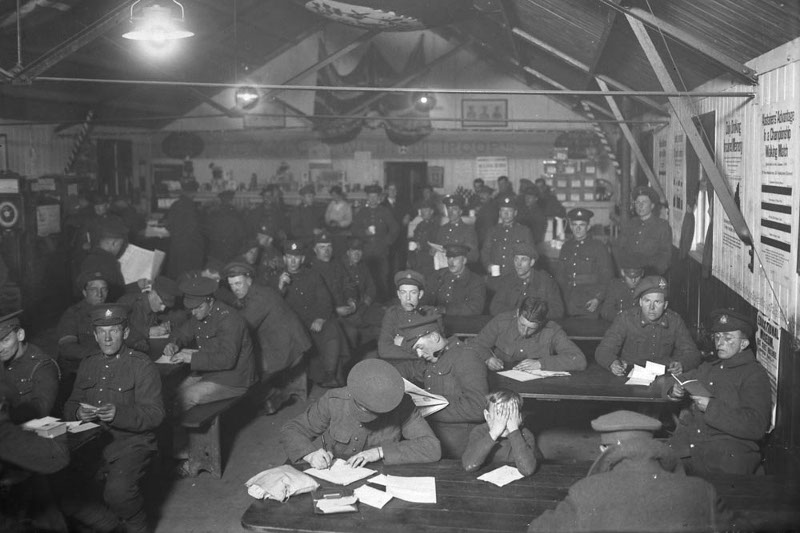

Photos of soldiers training from the National Archives of Canada.

Photos of soldiers training from the National Archives of Canada.

Much later, Jack enters the hospital with hydrocele, which is a swelling of the genitals. I assume that this was training/combat-related because nowhere in his records is it ever classified as “VDG” or “VDS.” Hydrocele is a relatively common injury for men in the military; and, can be caused by injuries sustained during hand-to-hand training… exasperated by the wet trench environment.

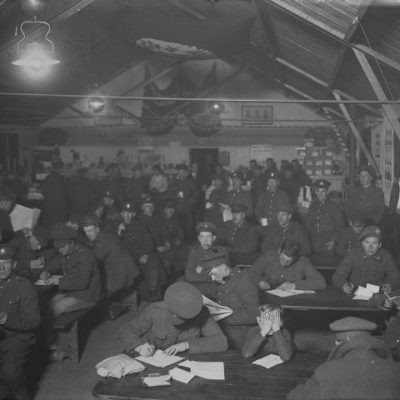

For the men in Bramshott, they often spent their downtime at one of the handfuls of camp YMCAs. The Y (originally from England) served to bring entertainment to the troops and simultaneously promote the core Y principles (spirit, mind, and body); this meant providing sporting events, religious ceremonies, concerts, and a safe/clean place for men to play cards, write, and simply socialize with others.

From what I can tell, there were multiple YMCA buildings at Bramshott.

Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden’s Visit (March 1917)

As mentioned above, when news got back to Canada about the miserable living conditions in the overseas Canadian training camps, officials headed to England to investigate and negotiate an improved situation. As part of this, Sir Robert Borden did a troop inspection at the camp on March 29, 1917.

Max, Amos, Jack, and Arthur were in Bramshott during this troop inspection. Archie had already left for the front on March 5th, 1917.

This was one of the few opportunities where the Canadian government allowed the use of video and photography (banned in late 1916… on the eve of conscription); the video shot was then used in propaganda videos and played in small theatres around Canada so families could see video images of their loved ones training for war.

In his speech before the House of Commons on May 18, 1917, Borden states that In Great Britain I visited eight camps in all: Shorncliffe, Crowborough, Shoreham, Seaford, Witley, Bramshott, Hastings, and in Windsor Great Park, a camp of the Canadian Forestry Corps. I found the men in good spirits, in good physical condition, and undergoing careful and effective training; at least it seemed to me excellent.

Again, Borden’s speech comes on the eve of conscription in Canada…

The Remembrance Series

But wait… there’s more! The following posts follow the Mill Village Boys on their journey through the war.

World War 1: The Mill Village Boys (Part 1)

World War 1: the 209th Waiting in Swift Current (Part 2)

World War 1: the 209th Training at Camp Hughes (Part 3)

World War 1: the 209th Waiting in Digby (Part 4)

World War 1: the 209th’s Journey and Arrival Overseas (Part 5)

World War 1: the 9th Battalion in Shorncliffe (Part 6)

World War 1: the 9th Reserve in Bramshott (Part 7)

World War 1: Taken on Strength… to France (Part 8)

Arleux-en-Gohelle (a.k.a Finding Max)

The Dominion British Cemetery (a.k.a. Finding Jack)

0 comments on “World War 1: The 9th Reserve in Bramshott (Part 7)”Add yours →