This is the sixth post in a series about a group of World War 1 soldiers from Mill Village, Nova Scotia who all enlisted for the 209th Battalion in Swift Current, Saskatchewan. For full context and more information about the people below, Part 1 is here. There is also a remembrance page with links to all the posts in this series, which can be found here.

A Note on Researching the 209th

I spent months and months and months sifting through historical records, examining photos, contacting archivists/museums (who rarely ever reply… which is ok… I’m a history geek, I understand being lost in your head); and, in going through all these historical records the one thing I’ve discovered is that when researching the 209th the record was haphazard. It was very amateur and non-military. Records were missing, the proper protocol was not followed, and it was only through their missteps that I was able to pull together a story.

That story rarely ever called out our Cabri/Mill Village men because they were good men and rarely got into trouble. And, whenever I followed a breadcrumb to a “mention”… it would be missing from the file.

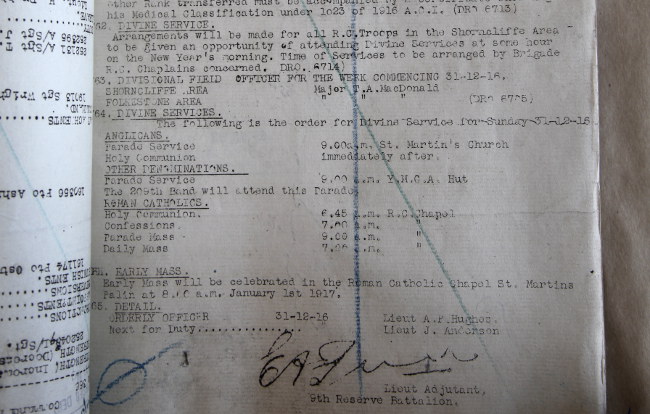

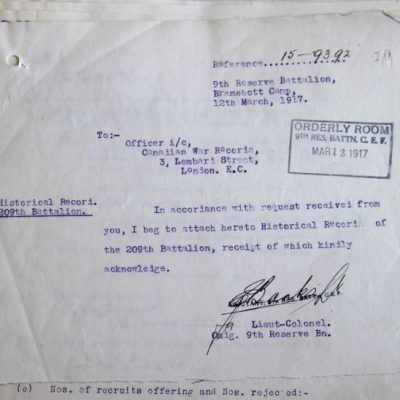

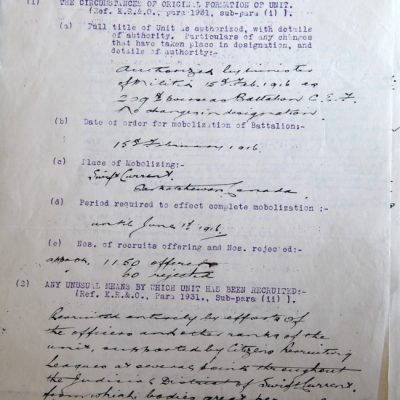

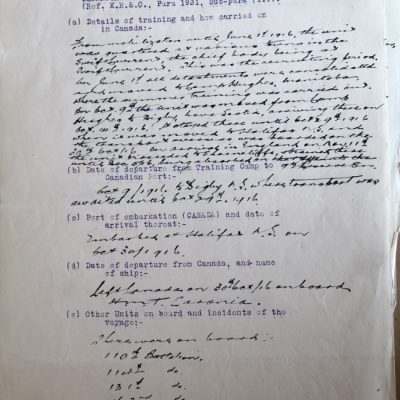

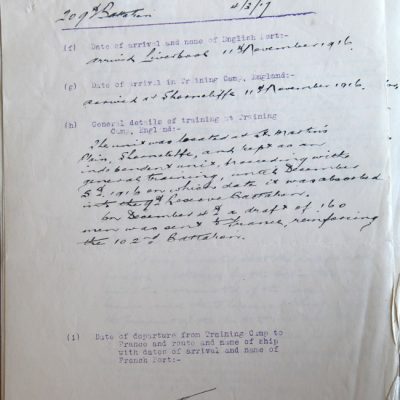

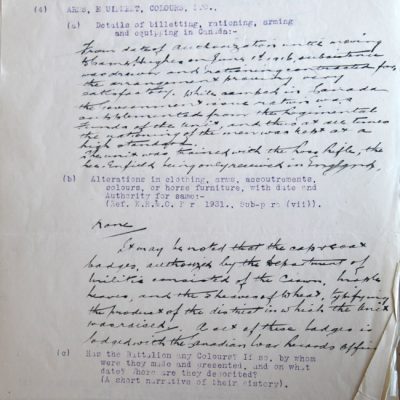

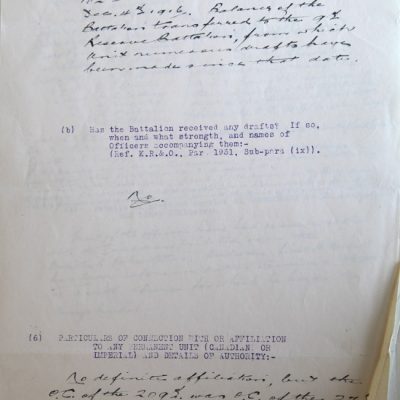

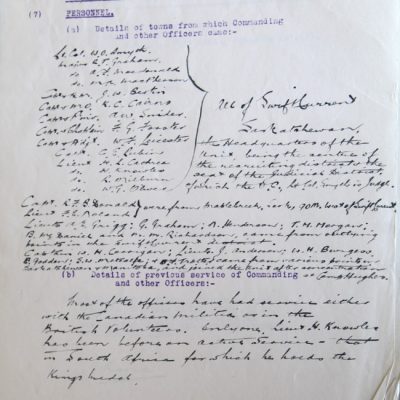

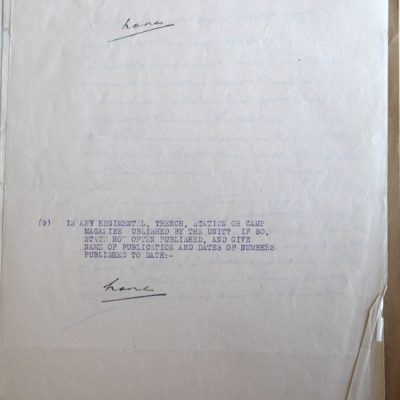

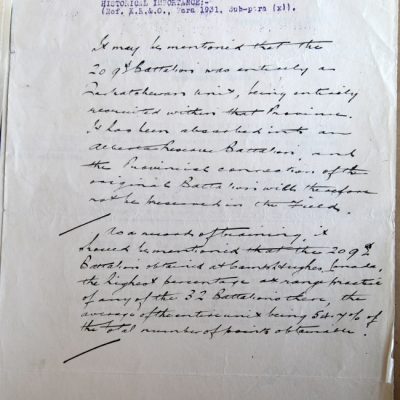

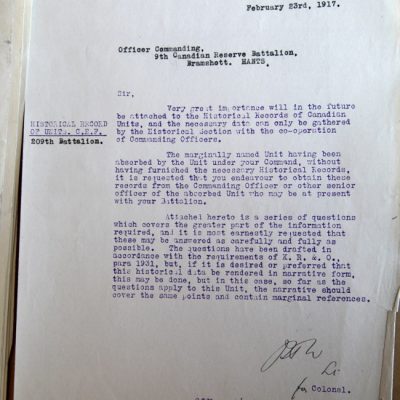

However, when the Battalion was absorbed by the 9th Reserve Battalion (January 1917), the record became militarized; meaning, there were standard records that need to be kept and these are meticulous. The first record retroactively created was the 209th Battalion Historical Record.

As a new researcher, I would start by reading this to get a fundamental understanding of the battalion’s history (each photo is larger than it appears in the gallery so it should be readable).

After gaining access to the 9th Reserve Battalion records, I started to see periodic mention of the Cabri/Mill Village men in the Daily Orders.

Measles, Mumps, and Rubella

As mentioned in the previous post, on arrival in England it was not uncommon for soldiers to fall victim to those childhood diseases that most modern kids are immunized for: diphtheria, smallpox, chickenpox, rubella, and measles.

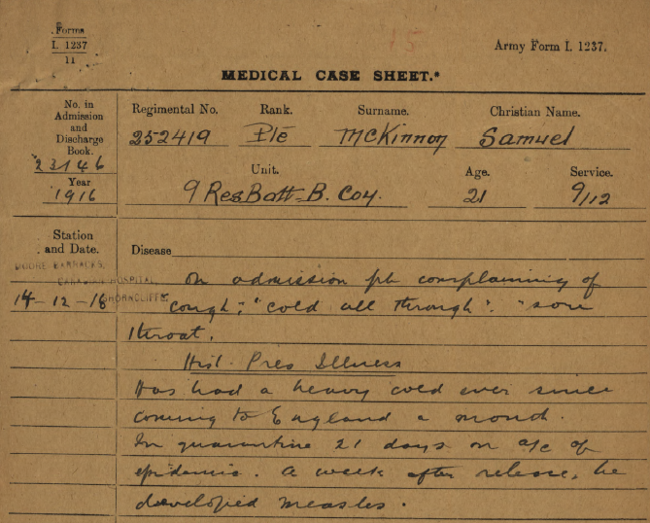

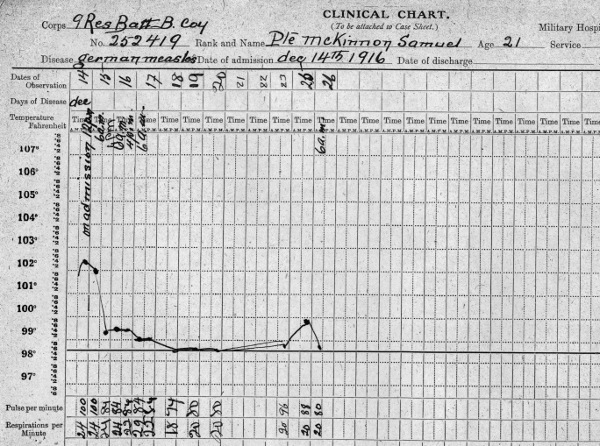

Max was no exception and on December 14, 1916, he was admitted to Moore Barracks Hospital (in Shorncliffe) complaining of a cough, sore throat, and feeling “cold all through.” He claims he had a “heavy cold ever since coming to England” and a week after release from a camp-wide quarantine, he developed rubella. Max gave the doctor a medical history that included tonsillitis, pertussis, measles, and scarlet fever.

From the McKinnon family personal records.

From the McKinnon family personal records.

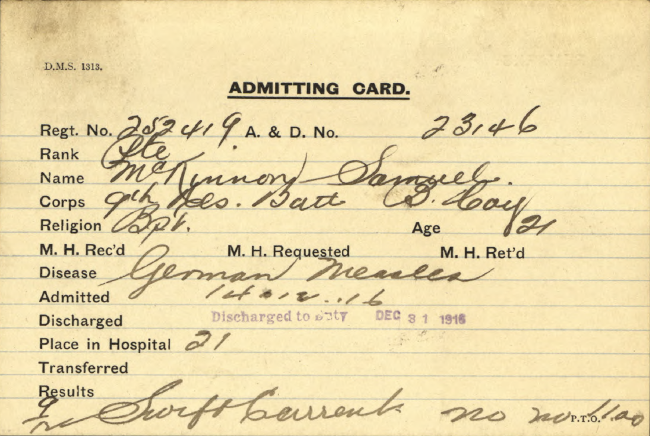

On admission, Max was given place number “21” in the hospital. He was one of the 26-men who were admitted that day.

From the McKinnon family personal records.

From the McKinnon family personal records.

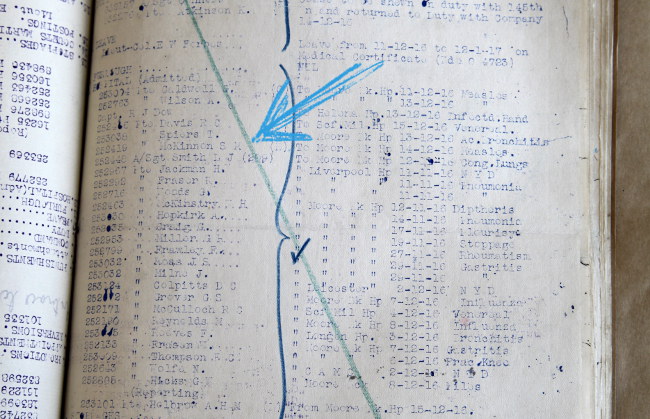

From the National Archives. Photo taken by Sharlene McKinnon.

From the National Archives. Photo taken by Sharlene McKinnon.

It’s not surprising that so many men were sick. The weather in Blighty during this period is noted as being was rather miserable with non-stop rain. On December 16, 1916, James Bowes from Winnipeg writes, “It has rained practically every day since we came back from London. The light is awfully poor for shooting. In fact, we could hardly see the outline of the targets when we were shooting at the 400-yard range.”

His brother Fred writes, “If it gets any worse than this we will be web-footed by the time we get back.”

Private William H. Crapper of the 133rd Battalion writes, “…there is heaps of mud up to our knees at times, for it rains nearly every day, and the soil is a heavy clay so you can tell what the mud is like. We are sleeping in tents just now, and some of them leak. I went to bed the first night we were here, and wakened up and found that my kit bag had gone for a swim. Oh, it’s nothing to wake up and find one’s shoes half full of water. I am going to buy a hook and line and then I won’t have to get out in the mud after my things.”

The platoons were jammed into tents or small huts… two huts per platoon. Shorncliffe was overflowing with men, which was a great way to spread sickness.

Rather ironically, a few days later, the 209th Battalion doctor, K.C. Cairns was admitted to the same hospital with influenza, which was later determined to be pleurisy caused by latent, quiescent tuberculosis. He was deemed unfit for duty and immediately sent back to Canada.

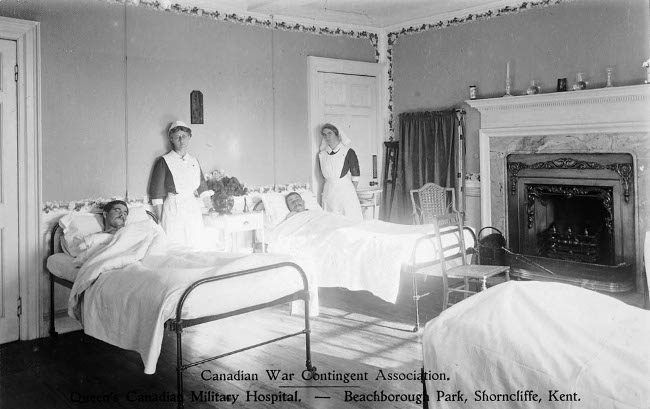

The hospital is one of the places where the men wanted to be. In the hospital it was clean, they had a comfortable bed, good quality food, constant attention from the doctors and nurses, and they were warm and dry. One of the best things that could happen to a soldier was to get shot… with a small, non-life threatening wound… so he could convalesce for months or be sent home a war hero.

Cliff Bowes writes during his hospital stay in 1916: “I am living like a lord here. Chicken and fish for supper and dinner; bacon and eggs for breakfast and two pints of stout a day, one at dinner and one at bedtime.”

Photo from the National Archives.

Photo from the National Archives.

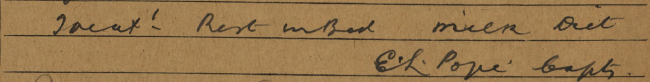

For rubella, Max was put on a “milk diet” and prescribed bed rest.

From the McKinnon family personal records.

From the McKinnon family personal records.

In the early 1900s, raw milk was seen as a curative for disease and doctors frequently prescribed raw buttermilk to sick patients. It was warmed and sipped in small amounts throughout the day.

The “milk diet” must have worked because there was an almost immediate drop in fever.

From the McKinnon family personal records.

From the McKinnon family personal records.

Max spent a total of 18-days in the hospital and suffered no complications from the disease. This means he was in the hospital for Christmas but was out just in time for New Year’s Eve. None of the other Cabri/Mill Village men were hospitalized; it’s likely they spent their time doing drills and training.

Christmas and New Year’s

During the Great War, it was an accepted practice for the Allies and Germans to have a ceasefire on Christmas Day… usually followed by a frenzied exchange of mementos in no man’s land and a friendly game of footie on the muddy field.

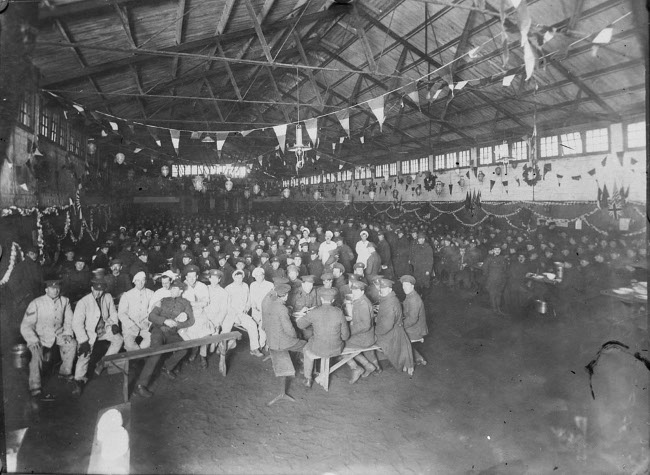

For those troops who were not on the front, they were entertained at the YMCA by local groups, the Canadian military’s version of a Pierrot Troupe, and one of the many military bands. This would like likely been preceded by a religious service.

Christmas at the YMCA Shorncliffe, 1916. Photo from the National Archives.

Christmas at the YMCA Shorncliffe, 1916. Photo from the National Archives.

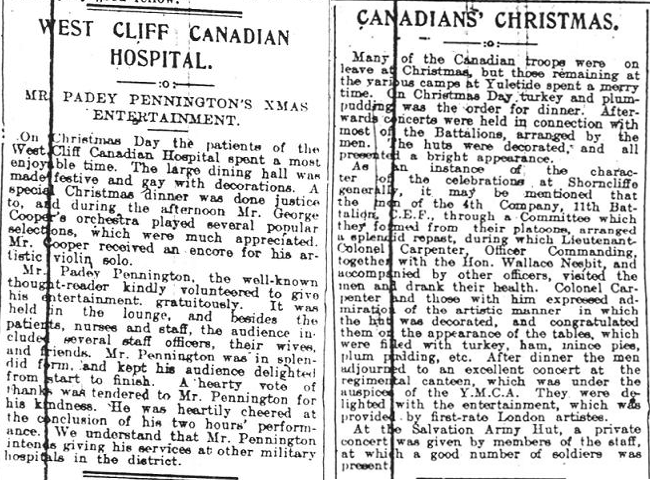

Men who were in the hospital like Max were entertained as well. The performer making the round at all the hospitals in December 1916 was Padey Pennington, a “well-known thought reader.”

Clippings from the Folkestone Herald, from an unknown source.

Clippings from the Folkestone Herald, from an unknown source.

Max was discharged to duty on December 31, 1916… just in time for New Year’s Eve celebrations, which was less “celebration” and more a “religious service” followed by a performance by the 209th Band (for those men who attended the non-Anglican or Catholic service).

From the National Archives. Photo taken by Sharlene McKinnon.

From the National Archives. Photo taken by Sharlene McKinnon.

The Remembrance Series

But wait… there’s more! The following posts follow the Mill Village Boys on their journey through the war.

World War 1: The Mill Village Boys (Part 1)

World War 1: the 209th Waiting in Swift Current (Part 2)

World War 1: the 209th Training at Camp Hughes (Part 3)

World War 1: the 209th Waiting in Digby (Part 4)

World War 1: the 209th’s Journey and Arrival Overseas (Part 5)

World War 1: the 9th Battalion in Shorncliffe (Part 6)

World War 1: the 9th Reserve in Bramshott (Part 7)

World War 1: Taken on Strength… to France (Part 8)

Arleux-en-Gohelle (a.k.a Finding Max)

The Dominion British Cemetery (a.k.a. Finding Jack)

0 comments on “World War 1: The 9th Battalion in Shorncliffe (Part 6)”Add yours →